The Benefits of Expanded Academia

Dr. Randy Lewis, Professor and Chair of American Studies

You’ve probably heard of expanded consciousness but have you heard of expanded academia? It’s less trippy but still pretty valuable— and it’s legal in the state of Texas!

Let me explain.

Last week Dr. Rebecca Peabody (Getty Museum) met with a few grad students in American Studies and History for a wonderful conversation about what she calls “expanded academia,” her phrase for the broader landscape of academic and quasi-academic jobs that exist beyond the tenure track paradigm.

I suspect that the room was filled with people who are trying to figure out if typical academic jobs make sense for them. Fortunately, Dr. Peabody had a lot of good advice. She encouraged us to recognize how many choices we can have if we are willing to work within a larger ecosystem.

Indeed, what I took away from her talk was how much agency we are leaving on the table when we decide to say “nothing matters except that tenure track job—I’ll take it no matter what the cost!” That sort of academic tunnel vision can limit our sense of what is possible with our PhD.

Where does that tunnel vision come from? Increasingly it’s not coming from faculty; for instance, our department has an incredible record of placing people in expanded academia over the past 40 years and has been immensely celebratory of all of the various outcomes. We have never valorized one outcome over another but perhaps the phrasing is part of the problem now; there is something odd about the expression “alt-ac” because, as Dr. Peabody points out, few people are “in or alt” in some simplistic either/or way. For most PhD’s, the career path is more serpentine than straight line.

After all, graduate work in American Studies can prepare us for positions in administration, advising, curation, journalism, and other fields. For this reason Dr. Peabody talked about the importance of “same preparation, multiple outcomes” rather than “preparing for one outcome.” She suggested that academic skills are very transferable—even more so than we expect. She also talked movingly about “iterative self-discovery as an important life skill” and how your feelings of self-doubt along the way are not a sign of weakness.

I loved the way she started by sharing her intellectual biography in a way that wasn’t about maximizing cultural capital: e.g., the “my many brilliant accomplishments!” model that you hear at many academic events (is vanity simply inverted insecurity?). Instead, she was explicit about filling in the gaps in her own CV to show what a circuitous route we often take to our jobs.

Is it easy? Of course not. She talked about the very real struggles of being a new PhD, filled with uncertainty about her job prospects but pretty certain that a standard academic position sounded like a deadline-infested drag. Like most people straight out of grad school, she said that she struggled at first. She talked about needing to write her book’s introduction in a two hour window at a Starbucks (which was as long as she could be away from her newborn twins), and about being a first generation college student in Iowa before landing in prestige machines like Yale and the Getty.

It’s important to hear stories like this. Relatively few people go from a PhD program to an amazing postdoc or an attractive TT job nowadays–it was always difficult but feels particularly tricky in 2022. Most people are like me: in the 1990s I worked in publishing in multiple positions, taught at different levels including a high school, worked in a museum, and even dabbled in journalism (well, I was an unpaid “contributing writer” for a NY magazine, which at the time seemed like it might be a career path). You can see these elements on my own CV, but not the fact that I also worked as a night janitor in a bank, a UAW organizer, an undergrad counselor, among other gigs—all before I took an assistant professorship (and all while trying to write and publish on the sly!).

Back then I was convinced that success was only possible if I landed an assistant prof gig, but reality is much more complex than such Manichean scenarios.

The upshot for me: maybe don’t put all your emotional eggs in one professional basket. There are so many ways to use the skills we gain in American Studies, and many of them (in my experience) offer as much or even more joy, community, and dignity than the often elusive TT line (and yes, it was elusive even in 1995!). Instead of having the narrow mindset of “I must grab any TT job that I can get, even if it’s in place that irritates me on every level,” think about what really matters to you.

This is why I appreciated it when Dr. Peabody talked about the importance of not letting your career be your number one priority in your life (to the extent that your circumstances allow. Economics are always weighing heavily on this matter). I get it. After spending 6+ years in grad school, it can be very hard to say “maybe I’ll end up teaching at a nice college or maybe I’ll do something else that is just as great.” But I recommend that flexible mindset when you embark on grad education in the humanities and social sciences. Giving yourself choices is the first step to actually having choices.

Obviously I found her talk very empowering—and was grateful to Annie Maxfield and the Texas Career Engagement office for making it happen!

Learning and Unlearning: Education in Flux

By Amanda Tovar, PhD Student in American Studies, UT-Austin

As a Latina who used to hate herself, Gloria Anzaldúa’s work challenged me to love myself. Additionally, her work propelled my journey in higher education. Her text Borderlands provided me the confidence I needed to see value in my lived experience to the point that it made its way into my work. But what does that mean in 2022 when valid critiques of her work have come to light? What does it mean that I read and used her work for so long but did not realize the problematics of her work?

For clarity, Gloria Anzaldúa’s work has come under fire recently for perpetuating Indigenous erasure via cultural appropriation. Likewise, her concept of mestiza consciousness stems from José Vasconcelos’ concept of raza cósmica (cosmic race), the result of mestizaje. La raza cósmica and mestizaje are both extremely racist and essentially call for the muting of Indigenous and Blackness for the sake of “one” “cosmic” race. There is no justification for using this, at all, in any way shape or form.

Admittedly and ashamedly, I wrote an introduction for an academic journal where I stated that Anzaldúa’s work “nourished my mestiza soul,” and not only is that CRINGEY for me now, but it is heartbreaking. Heartbreaking because I was so deep in my own world that I did not consider the real- life implications of a text that’s main theoretical concept upholds and perpetuates white supremacy.

For some time, I have wanted to hide my head in the sand and pretend that my previous writing and work did not exist, but that would be cowardly. Instead, I want to own the hurtful words I espoused and upheld and hold myself accountable for the sake of my own personal growth—academically and personally. Does this excuse me of my wrong doings? Absolutely not, but I want to be very intentional and honest with myself and others moving forward in my academic journey.

Being oblivious to the problematics of certain aspects of texts that I once regarded highly caused real harm to which I acknowledge fully. For some time, even, I “cancelled” myself to the extent of not producing or sharing my work with anyone outside of immediate professors because I felt immense shame in being someone who perpetuated harm. And then I came across Adrienne maree brown’s We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative Justice and it greatly shifted my perspective.

brown likens us (people) to mushrooms, all connected underneath the surface and states that the same is true about conflict and harm (brown, 8). She states that a toxic substance in our interconnectedness is supremacy, that is has been invisible to those who benefit from it and is “desirable” by those suffering from it—and that was true in my case and the case of many colonized brown folks (brown, 8). My proximity to whiteness bred problematic ideologies that allowed me to uphold mestizaje and mestiza consciousness as something to be celebrated. And again, nothing excuses it, but I am holding myself accountable and unlearning what I once knew.

While I can dig and dig and dig and expose the crux that lies beneath the metaphorical soil that is my lived experience, it is not enough. brown writes that “we need to flood the entire system with life- affirming principles and practices, to clear the channels between us of the toxicity of supremacy, to heal from the harms of a legacy of devaluing some lives and needs in order to indulge others” and I fully agree (brown, 8). We need to unlearn behaviors and information that we have been immersed in and begin anew. As brown suggests, I will tell people I have hurt people, I will do the work, I will learn new things, and I recognize that it is not too late (brown, 76). My education—personal, academic, and otherwise—is in constant flux.

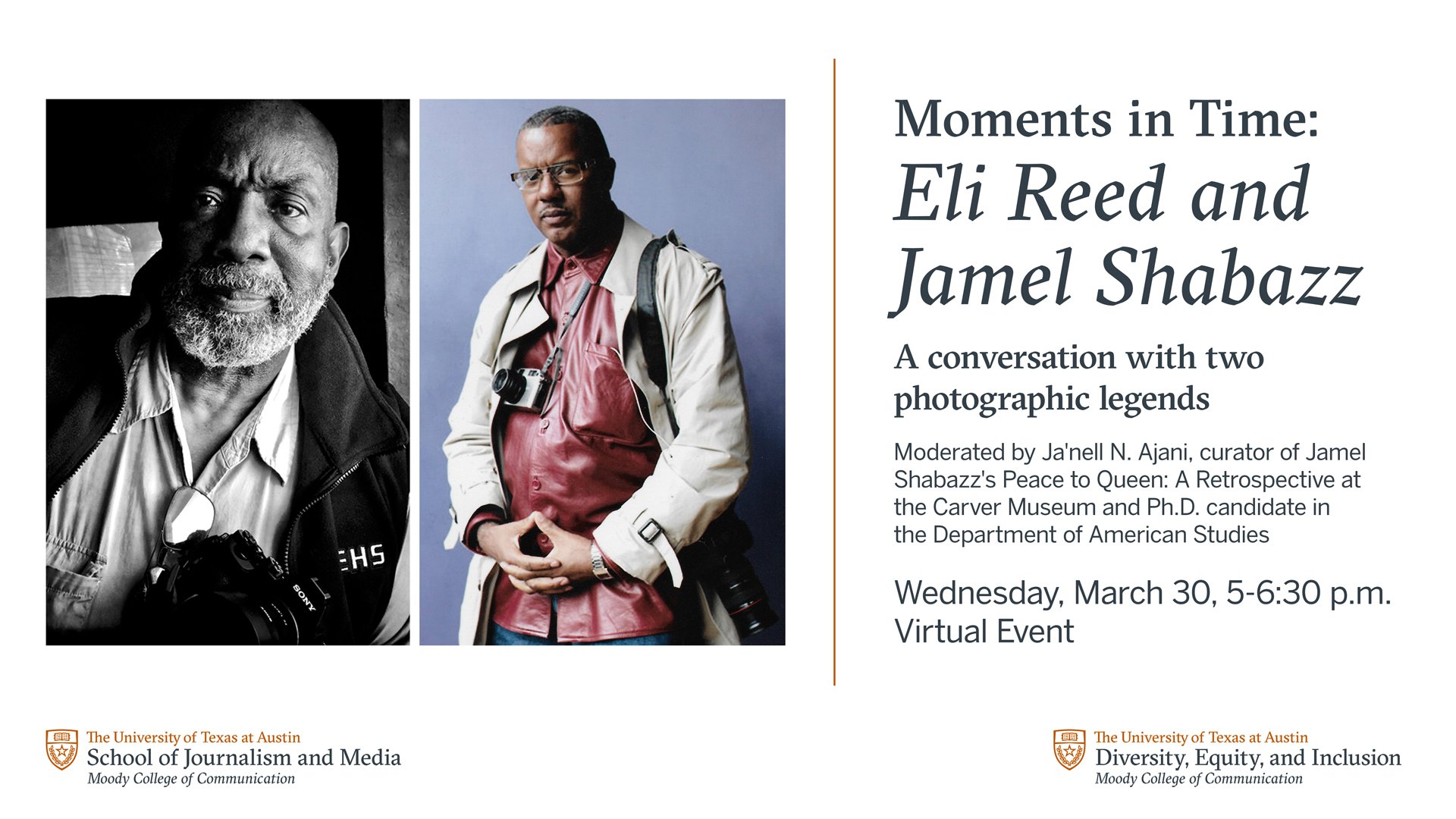

Moments in Time: Eli Reed and Jamel Shabazz

American Studies PhD student Ja’Nell N. Ajani will be moderating this conversation! Register here.

Experimental American Studies and the Elements of Marfa

photos + essay by randy lewis, chair and prof in the Department of American Studies, about one of the many exciting things going in UT American Studies: think of it as an invitation to create similar projects on other topics and in other places…

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Do you ever think about the endless intricacies of the periodic table? You do? Well, not me!

Yet lately I’ve been wondering if humanities scholars have something worth saying about helium, nickel, copper, lithium and the rest of the elemental stuff we haven’t investigated since high school chem? Can we write something vivid and meaningful about the elements that emphasizes the power of culture, history, and identity in areas far from our usual expertise? My answer is firm and clear: definitely maybe!

At least that’s what I was half-seriously thinking when I joined a new collaborative writing project on the elements dreamed into existence by anthropologists Marina Peterson (UT Anthro) and Gretchen Bakke (Humboldt University, Berlin). In the past few months the dozen or so members of the project have each selected a single element to write about, with others expected to join in the months ahead. Then with initial funding from a Texas Global Faculty Seed Grant, we met in Marfa for two days of fieldwork, planning, and workshopping, with the ultimate goal of producing a short essay on every element in the periodic table. Imagine 118 tiny books on the cultural lives of the elements and you’ll get the idea.

On the sublime road from Marfa to Fort Davis, home of the McDonald Observatory (all photos by author)

Well known for their research on various kinds of infrastructure and atmosphere, Marina and Gretchen planned out a judicious blend of structure and chaos for the weekend (an overly structured event is deadening; pure chaos is disorienting). The long stretch of communal time allowed for something that’s rare on campus during the Zoom age: we got to know each other a little bit. Marina rented a small architectural gem of a house where we met up with a pile of books, electronic gear, basic bookmaking equipment, and posters of the periodic table. My first thought is wow: this is cool but what the heck are we doing?

Some of the books Dr. Marina Peterson had brought for our collective inspiration

And that’s not a bad question to ask yourself at the beginning of any research project. In fact, this positive perplexity is why my favorite work happens in situ and especially in places like Marfa. As a grad student in the early 1990s, my first trip to Marfa hit me like a meteor of possibility. Back then Austin was much more shaggy than cosmopolitan, very far from the slick global brand that it is today—so much so that Marfa seemed like Soho in the desert on one particular weekend in 1991 when I showed up in my little Ford pickup. Claes Oldenburg was strolling around the grounds of the Chinati Foundation, Gus Van Sant’s short films were projected inside an empty swimming pool, random bagpipers wailed like angry cats in the dark, and a smattering of local ranchers stood around a bonfire gripping Shiner Bocks and wondering what to make of all the wildly dressed art students. Everyone was mingling at a free annual party held by the minimalist sculptor Donald Judd, who had been remaking the town since relocating from Manhattan in the 1970s.

This wonderful weekend planted a seed in my mind that Marfa was a special place for creative experimentation, while also giving me hope for a kind of lone star transformation that often seems out of reach. Because my own family has been in the state since the 1830s, mostly not transforming, not finding an easier way forward (for instance, this is my wonderful but excessively hard-working aunt), I am incredibly invested in ways that Texas can change for the better—and watching my sleepy slacker Austin becoming a glitzy Technopolis with an Apple campus, million dollar condos, and a massive Tesla factory is not really what I had in mind.

My own aspirations are closer to what I found in Presidio county ever since that initial trip in 1991. If dusty little Marfa can go from a sleepy ranch town to a global art mecca (not without its drawbacks, to be sure), then perhaps our state can evolve into something other than heat-baked sprawl, CRT-phobic suburbs, struggling small towns, and an ever-widening interstate system that eventually swallows us whole.

Happily, the elements project has a perfect crew for imagining something better, if only in a preliminary and exploratory way. Some familiar faces are in the room in our little Marfa HQ-–Lindsey Freeman (Simon Fraser U) is one of the most perceptive and graceful writers now in academia. Craig Campbell was there in his old Mazda pickup with Queen Elizabeth waving ironically from the window: if you are doing something at the nexus of art and anthropology, or anything that is just plain novel, cool, and brilliant, Craig is probably in the mix (as he was for the Carceral Edgelands Project earlier this year, and the Ex Situ Collective, which has met for similar projects in Austin, Windsor, Athens, and here in Marfa in 2014 for which we had to create work while in transit). Fusing art and scholarship into a collaborative and often accelerated process is always a revelation, and these academic experimenters are my core peeps, intellectually and temperamentally speaking, as much as American Studies.

Dr. Craig Campbell, UT Anthro, with his regal co-pilot

Looking across Marfa’s main drag with some ironic commentary for academics who love to talk!

So what was the experience like? I rolled into town, dusty and tired in the late afternoon. Within 30 minutes, I wandered into the coolest shop ever, run by a wonderful guy who I interviewed for my film on Prada Marfa last fall, whose interior designer partner told me mind blowing stories about the contemporary art scene in Mexico City; then I walked into a photo shoot for a catalog where they let me sit inside a 1953 Studebaker Commander; and was told that Lady Gaga was in town for a Dom Perignon shoot (alas, untrue!), while a friend was emailing me that Grimes and Chelsea Manning are dating back in ATX. That’s how Marfa is. If I walked around a corner and bigfoot was playing banjo with Miranda July and Harvey Keitel with Beyoncé at the conductor's podium, I would have been like “sure… that makes sense.”

Marfa is heaven for people who love old trucks and cars (as the author does!). The elements (in another sense) weigh heavily on machines, houses, and people in West Texas.

For the next 48 hours I worked alongside various participants, watched a dirt devil rip off a big section of a roof, and prayed for the wind to die down because the swirling ragweed was hitting me like a thousand hangovers. At night we donned six layers of clothing and drove to the McDonald Observatory, which is one of the greatest appendages of the UT world. I peered through telescopes and saw Orion’s Belt, lunar close ups, and hazy nebulae, while the astronomers nerded out on our dopey questions. So many brilliant minds in the Davis mountains figuring out the universe—astronomers have to have the souls of poets, right? Perhaps the question for our gang is the obverse: do poets have the souls of astronomers?

An oblique form of inspiration bubbles up as we approach helium, hydrogen, lithium, and the rest of the cosmic stew in our own cult studies way, hoping to create micro books on individual elements. Mine is dedicated to lithium, about which I knew nothing last year. Now I is expert! (I’m riffing off an old engineering joke). For weeks I've been reading about its applications: the batteries of Elon Musk, the mental health of Brittney Spears, the music of Kurt Cobain. It’s in fireworks, pacemakers, lubricants, hydrogen bombs—everything seems to need it nowadays.

One surprise about driving from Marfa to ATX along the border is the extraordinary beauty of the Pecos Canyon Bridge, with hundreds of wild goats far in the distance. If we blew up the photo, you’d see them on the right side of the river.

The Elements crew took a field trip to Shafter, a nearby ghost town now where 2000 miners are buried. Almost no one lives there today, but we met a happy couple who had been residents for 30 years.

We kicked around another element in the morning, driving an hour south to take notes around a dead silver mine in Shafter, Texas, almost on the border. Megan Gette, a talented graduate student from anthropology with a creative writing background, used hydrophones and contact mics to record the ghostly sounds of metal and dirt. She let me listen to her headphones and I was shocked: a metal fence sounds like a didgeridoo when you tap it softly.

Group work is messy by necessity. Back in town we gently argue for an hour about what to call the publications. Over the course of two days we plan, write, design, cut and fold dozens of prototypes (one participant says it’s a bit like elementary school). It’s not all forward progress and it may not yield a consistent neoliberal knowledge-nugget with quantifiable “impact factor,” and yet I look around the room and see my favorite model of academic life. Anthropologists, humanists, sociologists, and poets. Lots of movement, lots of dialogue, lots of snacking. A lot of group work, DIY fashioning, and a handmade product that is about the creation of new forms of knowledge.

Co-organizer Gretchen Bakke from Berlin, along with Megan Gette and Monti Sigg from Austin

Not surprisingly, I start thinking of it as “artisanal academia.” Chaos and brilliance simmering on the stove together: it’s exhausting but convivial work that will yield an atypical academic “product.” Given the overproduction of standard journal articles that often go unread or quickly obsolete, I’m fascinated by our embrace of the ephemeral: we are in the realm of experimentation, collaboration, and innovation in form (which often happens when artists are injected into academic settings, or when you work with academics who are also artists/poets).

Pondering the elements!

The trailer park that never happened, near the ghost town of Shafter, which has an amazing local history center with fascinating information on display. Only a few people live nearby where once thousands lived and died in pursuit of silver (atomic number 47).

The reality of Marfa is a profound visual inconsistency in the built environment. It’s a rapidly gentrifying town where a NY investment banker might own a million dollar third home that they almost never visit—and it’s often right across from a house like the one above in the heart of town. Hyper-modern homes with lap pools and fragile leftovers are juxtaposed on Marfa’s streets, more so than anywhere I’ve ever been in the US. See Kathleen Shafer’s book on Marfa for more on the town’s history.

So that’s what I did for the first few days of Spring Break. People hear the word Marfa and they probably think minimalist art vacation or something—and it was in the sense of being out of the normal traffic and hustle of the violet crown.

Near the abandoned silver mine of Shafter, searching for inspiration and/or a cell signal

But it’s also not nothing to drive 1000 miles in four days and take part in an ambitious collective experience, sustained mostly by the quality of the minds and the idealism of the people around you. I was exhausted when I rolled back into ATX, immediately sprinting to catch a bullet train of bureaucratic obligation. Squeezing back into my little work silo to manipulate symbols that flicker across multiple screens with endless continuity, simultaneously dulled and jittery, social but alone, I’m already thinking about the wildness and possibility in the elements of Marfa.

The great sociologist Lindsey Freeman, a Tennessean now in Vancouver, and the author of This Atom Bomb in Me and Longing for the Bomb

The author looking ready for the wind apocalypse in Shafter, with photographer Monti Sigg

The importance of snacks and wine to intellectual work can never be underestimated!

Traveling Back in Time to “Weird Austin:” Daniel Johnston “I Live My Broken Dreams

by Holly Genovese

Photos also by Holly Genovese

I’m not from Austin, or Texas, and before moving here in 2018 to study I had visited once, for 24 hours. I knew Austin had a reputation for being cool, but I couldn’t have told you why. I’m from the East Coast, and one thing I’ve realized since moving to Texas is that the East Coast thinks a lot of itself. We learn very little about anything west of the Mississippi and I only realized that when I left. I’m not from New York, not even close, but the “View of the World from 9th Avenue” cover of the New Yorker feels very relevant.

I didn’t know Austin used to be weird or that the city really loves movies or that so many famous people live here. I had no idea. I quickly realized that the “weird” identity of the city had all but disappeared decades before I arrived. Sure, there were the stickers. But it was difficult for me, moving to the city in 2018, to even understand what it was that Austin had lost. I knew it as a booming tech city, increasingly overpriced. I knew that it was incredibly white and getting whiter all the time. I knew that more and more tech moguls and celebrities were moving here. But much of the cool stuff had already been lost. I missed the last gasps of Austin as a hub for weirdos and creatives and moved here when it was already really hard to survive as a weirdo or creative (or a student, like me). To me, Houston, with its food scene and museums and Parts Unknown episode seemed like a real weird, creative city.

Even though I got here too late, there were still closures that hurt. The loss of our two video stores, Vulcan Video and I Luv Video, hit me hard. And the pandemic closure of Spiderhouse Cafe, which I didn’t learn about for months. And I’ve slowly discovered the places that do make Austin special–AFS, for one. Austin City Limits. The many independent bookstores, including Bookwoman, which has been around for 40ish years. But what really showed me what Austin once was, and never could be again, was the Daniel Johnston exhibition at The Contemporary ATX. The exhibit focuses on Johnston’s legacy–both his connection to Austin as well as his artwork and music. Johnston was the quintessential Austin weirdo-handing out mixtapes with hand drawn art at the Mcdonalds on Campus (there was a McDonalds on campus?). He gave off tremendously low-fi vibes in the early 90s, even as he painted a famous mural and Kurt Cobain wore a shirt with his artwork on it.

The exhibition shows the evolution of his work, as well as his music, and even includes a recreation of his workspace. A piano surrounded by toys and comics and funky objects. His work asked big philosophical questions through comic inspired art (Johnston loved Marvel).

I don’t why, but seeing Johnston’s art, seeing what Johnston was able to create in Austin, finally showed me what was lost when Austin stopped being weird. The Sound Exchange, where Johnston painted his famous mural, has been closed for 20 years. Nearly a decade before that, it was voted the “Best Place to Buy into the Underground” by the Austin Chronicle. For many new Austinites, the Underground has never existed in Austin. But the Contemporary’s exhibit on Johnston gave me a way of seeing an Austin that, for me, would never exist.

You have four more days to see “Daniel Johnston: I Live My Broken Dreams” and it’s absolutely worth braving the SXSW crowds for the chance to travel back in time to cool, weird, Austin.

Contemporary Art in San Antonio 2022-A quick look from UT Am Studies

“As an American Studies department based in Austin, we are lucky to have San Antonio just an hour away. On my way back from a two day writing workshop in West Texas with 15 scholars from all over, and after pausing at Judge Roy Bean’s homestead in Langtry, I stopped to see contemporary art shows at the city’s main museum as well as the small but always interesting ARTPACE. The shows were so good that I thought I’d make a 4 minute video that would serve as a introduction to our students and anyone else who is curious. If you haven’t been to these places, or if you don’t know Wendy Red Star, now is a great time to head down I-35.” — Randy Lewis, Chair, Dept of American Studies

Third Thursday Weds March 23rd

Come learn about the Annual Sequels Conference as well as the E3W Review of Books, which many UT AMS students have worked on!

UT AMS Alum Dr Christine Capetola to Give Talk Today

Contact Dr. Capetola for access information,

Professor Janet Davis featured on “I Don’t Know About That”Podcast

AMS professor Janet Davis was recently featured on “I Don’t Know About That,” a podcast hosted by Jim Jefferies. For more on the podcast writ large, click here. To listen to Professor Davis’s episode on the circus specifically, you find it here!