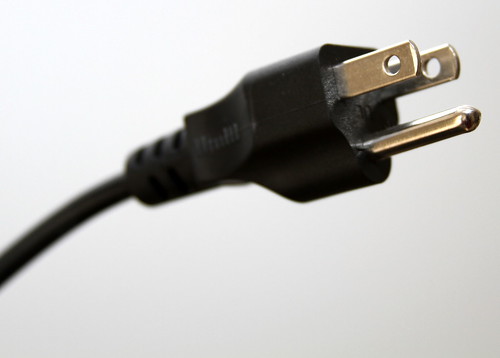

Faculty Research: Dr. Randy Lewis on Unplugging at Flow

Dr. Randy Lewis has a new piece over at Flow that questions why it is so difficult to imagine unplugging from the constant buzz of electronics that characterizes modern life:

Dr. Randy Lewis has a new piece over at Flow that questions why it is so difficult to imagine unplugging from the constant buzz of electronics that characterizes modern life:

Yet… are we not curious about how it would feel to experience the “great unplugging”? Would we relish the ensuing silence as we restore the old ways of communicating and connecting with one another? Or would we lapse into a languorous funk without Google and HBO, Avatar and Annoying Orange? Would we feel permanently stuck in the isolation tank of our own boredom, marooned with the hideousness of our own organic thoughts? Would we start sketching the “Real Housewives” on the walls of our condos in crayon, breathlessly narrating their erotic adventures like an ancient bards singing the tale Odysseus and the sirens? Would we pine for our iPhones, laptops, and flatscreen TVs like postmodern amputees cursing the loss of our cyborg appendages? Would we grieve for our machines?Probably. But what fascinates me is how loathe we are to even imagine this scenario. We are increasingly unwilling to contemplate the absence of the various screens that convey so much of our entertainment, sociality, and labor. Like Francis Fukuyama’s Cold War “End of History” argument in which capitalism’s apparent triumph over socialism foreclosed any discussion of alternatives, the new media juggernaut is so powerful that it has blotted out our ability to imagine anything else. We are all hopeless screenagers now.

I'm reminded here of a neuroscience experiment described at io9 last October:

A group of researchers from Germany and the UK designed a fairly complex psychological test to determine how people planned for negative events in the future. First, they asked the about the likelihood of 80 different disturbing events happening, such as contracting a fatal disease or being attacked. After they'd recorded people's responses, researchers told each subject the actual, statistical likelihood of such events happening. In some cases, people had overestimated the likelihood and in some cases they'd underestimated it.Then, after some time had passed, the researchers asked subjects again about the likelihood of these events happening to them. Interestingly, they found that people had a much harder time adjusting their expectations if the real-world statistical likelihood was higher than what they had first guessed. They had little trouble adjusting expectations for a more favorable outcome. It was as if people were selectively remembering the likelihoods of future events — forgetting the bad odds but not the good ones.

What does this mean? io9 sums it up nicely:

Basically, human optimism is a neurological bug that prevents us from remembering undesirable information about our odds of dying or being hurt. And that's why nobody ever believes the apocalypse is going to happen to them.

I think there are lessons to be drawn from these findings with respect to our reliance on technology, too. Perhaps our inability to imagine a world without these [im]material comforts, even though many of us actually lived in that world, is a chemical intervention to protect us. Because we are so individually and socially embedded in technology, maybe imagining the scenario of loss that Randy wonders about is too much for our grey matter to handle.Read the piece in its entirety here.