5 Questions with Dr. Lauren Gutterman

The Department of American Studies is very pleased to announce that Dr. Lauren Gutterman will be joining our faculty in the fall of 2015. Dr. Gutterman comes to us from the University of Michigan, where she is a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Society of Fellows. She holds a PhD in History from New York University, and has published in Gender & History and The Journal of Social History. Her current book manuscript, developed out of her dissertation, focuses on lived experiences of mid-20th century married women who desired other women. We spoke with Dr. Gutterman earlier this month, in advance of her arrival in Austin this August.UT AMS: What is your scholarly background and how does it motivate your teaching and research?Dr. Gutterman: I received my PhD in History at New York University, and I’m currently a postdoctoral scholar in Women’s Studies and the Society of Fellows at the University of Michigan. But my academic career really began as an undergraduate at Northwestern University where I double majored in American Studies and Gender Studies. Part of me will always be chasing the feelings I experienced as an undergrad as I learned to look at things—especially with regard to gender and sexuality—in an entirely new way. It just felt like the world was opening up, changing before my eyes, all these things that sound so trite but were completely true. As an undergrad I also discovered my love of history. I wrote a senior thesis about the New England Watch and Ward Society’s anti-burlesque campaign in the 1930s and that was my first experience with archival research. It was so exciting for me to read and touch things written so long ago, to try to see the world through someone else’s eyes. I discovered the depth of my nerdiness.As a teacher and a researcher, I’m most passionate about understanding how what we think of as normal and natural in terms of gender and sexuality has changed over time. My classes (like my research) combine a study of politics and popular culture in American history. In the fall I’ll be offering a course called “Sexuality, Reproduction, and American Social Movements,” which I’ve taught twice before at the University of Michigan. One of the things I enjoy most about this course is challenging students’ belief that women’s reproductive rights keep improving steadily with time. So, for example, we read about how abortion was unstigmatized, legal, and often easily accessible for most of the 19th century. There’s an oral history interview I use on History Matters with a working-class immigrant woman who got twelve abortions at the turn of the twentieth century in New York City safely, and without thinking anything of it; this is completely shocking for students.In addition, one of my major goals as a scholar has been to try to speak to a broad audience, to engage those beyond the academic world in the history of sexuality. I’ve tried to do this in multiple ways, through my work with the history of sexuality websites OutHistory.org and Notches, the Pop-Up Museum of Queer History, and the Center for LGBTQ Studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY. One of my proudest moments was discovering that artist Elvis Bakaitis had cited my work in a zine about 1950s queer history.What projects or people have inspired your work?Like many historians of homosexuality, George Chauncey's Gay New York is probably the one book that has had the greatest impact on my work. I first read it as an undergraduate and I remember being awed both by the extent and details of the queer world he uncovered, and by the simple fact that it was possible to do this kind of history.My current project, which examines the lives of wives who desired women since the postwar period, is in some ways a response to Chauncey's book which focuses primarily on men and on the public sphere. I don't believe that lesbians have ever had the same claims to public space that gay or queer men have had (even today there are far fewer lesbian bars), but this has not prevented women from engaging in sexual relationships with each other. My book project argues, in part, that the nuclear family household has functioned as a lesbian or queer space for married women; the women in my study typically engaged in same-sex affairs with other wives and mothers they met in the course of their daily lives, within their own homes.What was your favorite project to work on and why?I'm still working on revising my first book manuscript Her Neighbor's Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire within Marriage, which is based on my dissertation, so it is hard to talk about having a "favorite" project, since I don't have many to choose from!I can, however, speak to a favorite moment in researching this project, which occurred when I first went to the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco to look at the papers of Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. Martin and Lyon were long-time lesbian activists who helped found the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the nation's first lesbian rights group in 1955. When I first set out on this project, I imagined that I would focus on the lives of three women, one of whom was Del Martin. When I got to the GLBT Historical Society the materials I'd hoped would be there--about her personal life while she was married--were not, but I did discover dozens and dozens of letters that married women had written to the DOB and to Martin and Lyon stretching from the 1950s to the 1980s. Discovering those letters changed the entire frame of my project, because I realized I could write a social history (rather than a group biography) about these women, which I had not imagined before. I joked at the time it was like a finding a dissertation in a box.How do you see your work fitting in with broader conversations in academia and beyond?Well, I'll start with academia because that's easier...One of the things I am trying to do as a scholar is to draw attention to the ways that the history of homosexuality is primarily based on men's experiences. This problem cannot be addressed simply by taking our current model of gay history and "adding" women. I believe that focusing on women's lives can change our understanding of the history of homosexuality as a whole. For example (as I alluded to above), as long as the history of homosexuality focuses on the public sphere--on bars and public sex, and even government policing--women will inevitably play a lesser role within it. To make women more central to the history of homosexuality requires that we pay much more attention to the domestic sphere, as I do in my book. But this is just one of the ways that I think gay history might change by centering women's lives.Beyond the academic world, my work obviously relates to the broader conversation about gay marriage. My work shows that legally defining marriage as "between one man and one woman" cannot, and has not, ensured marriage’s straightness. Even in the postwar period--when American marriages were more widespread and longer-lasting than ever before--wives who desired women found myriad ways to balance marriage with lesbian affairs. Often these women did so by engaging in same-sex affairs in secret, but many women did not hide their affairs from their husbands entirely, and many husbands were willing to turn a blind eye to their wives' special friendships, and just wait for them to pass. In this way, my work shows that the histories of marriage and of homosexuality have long been intertwined, and that, in a way, marriage has been queer for much longer than we’d like to think.What projects are you excited about working on in the future?Over the last year or so, with the help of two incredible undergraduate research assistants at the University of Michigan, I've begun researching and writing about the case of Jeannace June Freeman, the first woman sentenced to death in Oregon in 1961. Freeman was a white, working-class, butch lesbian and she and her lover, Gertrude Nunez Jackson, together murdered Jackson's two young children in an incredibly brutal way. Based on everything we know about stereotypes about violent, mannish lesbians from the work of Lisa Duggan among other scholars, and about the discrimination homosexuals faced in the middle of the twentieth century, the fact that Freeman was sentenced to death is not at all surprising. What is surprising, however, (and this is what has fascinated me about this very disturbing case), is that Freeman became the major symbol of the movement to abolish capital punishment in Oregon, and many Oregonians came to see her as sympathetic. Ultimately, in large part because of her case, voters repealed the death penalty in Oregon in 1964 by referendum, and the governor commuted Freeman's sentence to life in prison. So the question that has been guiding this project is, why and how did Oregonians come to see a butch, lesbian, child-killer as deserving of mercy?At the meta level, though, this project is also about resisting the pressures that historians of homosexuality face to do history that is always somehow “good” for LGBT politics. Obviously, the field of sexuality history is fundamentally linked to the emergence of the gay liberation and women's liberation movements of the 1970s. And my own commitment to researching and writing the history of homosexuality is shaped by my political concerns, my desire to show that this history matters. But at the same time, I don't think it is good or honest to neglect those parts of the gay past we'd prefer to keep hidden. Jeannace June Freeman's case certainly lent credence to the worst stereotypes about lesbians at midcentury, but when we ignore her story—or those of other "bad queers"—we lose opportunities for historical insight and we surrender our ability as scholars to help contextualize some of the ugliest parts of the queer past. I don't think we can overcome homophobic stereotypes by tiptoeing around them.Bonus question – in one sentence, what is American Studies to you?To me, American Studies is the study of what it means and what it has meant to be American. Who gets to choose? Who gets excluded? What cultural and political mechanisms enable those exclusions? And how have they changed over time? In addition, for me American Studies is as much about the research method as the object; it's about a commitment to interdisciplinary work, however complicated or difficult that may be.

The Department of American Studies is very pleased to announce that Dr. Lauren Gutterman will be joining our faculty in the fall of 2015. Dr. Gutterman comes to us from the University of Michigan, where she is a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Society of Fellows. She holds a PhD in History from New York University, and has published in Gender & History and The Journal of Social History. Her current book manuscript, developed out of her dissertation, focuses on lived experiences of mid-20th century married women who desired other women. We spoke with Dr. Gutterman earlier this month, in advance of her arrival in Austin this August.UT AMS: What is your scholarly background and how does it motivate your teaching and research?Dr. Gutterman: I received my PhD in History at New York University, and I’m currently a postdoctoral scholar in Women’s Studies and the Society of Fellows at the University of Michigan. But my academic career really began as an undergraduate at Northwestern University where I double majored in American Studies and Gender Studies. Part of me will always be chasing the feelings I experienced as an undergrad as I learned to look at things—especially with regard to gender and sexuality—in an entirely new way. It just felt like the world was opening up, changing before my eyes, all these things that sound so trite but were completely true. As an undergrad I also discovered my love of history. I wrote a senior thesis about the New England Watch and Ward Society’s anti-burlesque campaign in the 1930s and that was my first experience with archival research. It was so exciting for me to read and touch things written so long ago, to try to see the world through someone else’s eyes. I discovered the depth of my nerdiness.As a teacher and a researcher, I’m most passionate about understanding how what we think of as normal and natural in terms of gender and sexuality has changed over time. My classes (like my research) combine a study of politics and popular culture in American history. In the fall I’ll be offering a course called “Sexuality, Reproduction, and American Social Movements,” which I’ve taught twice before at the University of Michigan. One of the things I enjoy most about this course is challenging students’ belief that women’s reproductive rights keep improving steadily with time. So, for example, we read about how abortion was unstigmatized, legal, and often easily accessible for most of the 19th century. There’s an oral history interview I use on History Matters with a working-class immigrant woman who got twelve abortions at the turn of the twentieth century in New York City safely, and without thinking anything of it; this is completely shocking for students.In addition, one of my major goals as a scholar has been to try to speak to a broad audience, to engage those beyond the academic world in the history of sexuality. I’ve tried to do this in multiple ways, through my work with the history of sexuality websites OutHistory.org and Notches, the Pop-Up Museum of Queer History, and the Center for LGBTQ Studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY. One of my proudest moments was discovering that artist Elvis Bakaitis had cited my work in a zine about 1950s queer history.What projects or people have inspired your work?Like many historians of homosexuality, George Chauncey's Gay New York is probably the one book that has had the greatest impact on my work. I first read it as an undergraduate and I remember being awed both by the extent and details of the queer world he uncovered, and by the simple fact that it was possible to do this kind of history.My current project, which examines the lives of wives who desired women since the postwar period, is in some ways a response to Chauncey's book which focuses primarily on men and on the public sphere. I don't believe that lesbians have ever had the same claims to public space that gay or queer men have had (even today there are far fewer lesbian bars), but this has not prevented women from engaging in sexual relationships with each other. My book project argues, in part, that the nuclear family household has functioned as a lesbian or queer space for married women; the women in my study typically engaged in same-sex affairs with other wives and mothers they met in the course of their daily lives, within their own homes.What was your favorite project to work on and why?I'm still working on revising my first book manuscript Her Neighbor's Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire within Marriage, which is based on my dissertation, so it is hard to talk about having a "favorite" project, since I don't have many to choose from!I can, however, speak to a favorite moment in researching this project, which occurred when I first went to the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco to look at the papers of Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. Martin and Lyon were long-time lesbian activists who helped found the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the nation's first lesbian rights group in 1955. When I first set out on this project, I imagined that I would focus on the lives of three women, one of whom was Del Martin. When I got to the GLBT Historical Society the materials I'd hoped would be there--about her personal life while she was married--were not, but I did discover dozens and dozens of letters that married women had written to the DOB and to Martin and Lyon stretching from the 1950s to the 1980s. Discovering those letters changed the entire frame of my project, because I realized I could write a social history (rather than a group biography) about these women, which I had not imagined before. I joked at the time it was like a finding a dissertation in a box.How do you see your work fitting in with broader conversations in academia and beyond?Well, I'll start with academia because that's easier...One of the things I am trying to do as a scholar is to draw attention to the ways that the history of homosexuality is primarily based on men's experiences. This problem cannot be addressed simply by taking our current model of gay history and "adding" women. I believe that focusing on women's lives can change our understanding of the history of homosexuality as a whole. For example (as I alluded to above), as long as the history of homosexuality focuses on the public sphere--on bars and public sex, and even government policing--women will inevitably play a lesser role within it. To make women more central to the history of homosexuality requires that we pay much more attention to the domestic sphere, as I do in my book. But this is just one of the ways that I think gay history might change by centering women's lives.Beyond the academic world, my work obviously relates to the broader conversation about gay marriage. My work shows that legally defining marriage as "between one man and one woman" cannot, and has not, ensured marriage’s straightness. Even in the postwar period--when American marriages were more widespread and longer-lasting than ever before--wives who desired women found myriad ways to balance marriage with lesbian affairs. Often these women did so by engaging in same-sex affairs in secret, but many women did not hide their affairs from their husbands entirely, and many husbands were willing to turn a blind eye to their wives' special friendships, and just wait for them to pass. In this way, my work shows that the histories of marriage and of homosexuality have long been intertwined, and that, in a way, marriage has been queer for much longer than we’d like to think.What projects are you excited about working on in the future?Over the last year or so, with the help of two incredible undergraduate research assistants at the University of Michigan, I've begun researching and writing about the case of Jeannace June Freeman, the first woman sentenced to death in Oregon in 1961. Freeman was a white, working-class, butch lesbian and she and her lover, Gertrude Nunez Jackson, together murdered Jackson's two young children in an incredibly brutal way. Based on everything we know about stereotypes about violent, mannish lesbians from the work of Lisa Duggan among other scholars, and about the discrimination homosexuals faced in the middle of the twentieth century, the fact that Freeman was sentenced to death is not at all surprising. What is surprising, however, (and this is what has fascinated me about this very disturbing case), is that Freeman became the major symbol of the movement to abolish capital punishment in Oregon, and many Oregonians came to see her as sympathetic. Ultimately, in large part because of her case, voters repealed the death penalty in Oregon in 1964 by referendum, and the governor commuted Freeman's sentence to life in prison. So the question that has been guiding this project is, why and how did Oregonians come to see a butch, lesbian, child-killer as deserving of mercy?At the meta level, though, this project is also about resisting the pressures that historians of homosexuality face to do history that is always somehow “good” for LGBT politics. Obviously, the field of sexuality history is fundamentally linked to the emergence of the gay liberation and women's liberation movements of the 1970s. And my own commitment to researching and writing the history of homosexuality is shaped by my political concerns, my desire to show that this history matters. But at the same time, I don't think it is good or honest to neglect those parts of the gay past we'd prefer to keep hidden. Jeannace June Freeman's case certainly lent credence to the worst stereotypes about lesbians at midcentury, but when we ignore her story—or those of other "bad queers"—we lose opportunities for historical insight and we surrender our ability as scholars to help contextualize some of the ugliest parts of the queer past. I don't think we can overcome homophobic stereotypes by tiptoeing around them.Bonus question – in one sentence, what is American Studies to you?To me, American Studies is the study of what it means and what it has meant to be American. Who gets to choose? Who gets excluded? What cultural and political mechanisms enable those exclusions? And how have they changed over time? In addition, for me American Studies is as much about the research method as the object; it's about a commitment to interdisciplinary work, however complicated or difficult that may be.

Undergraduate Research: Andrea Gustavson on teaching undergraduates at the Harry Ransom Center

We love it when we can draw your attention to the awesome teaching our grad students do and the exciting research our undergraduates do. Today, we'd like to point you toward the Harry Ransom Center's newsletter, Ransom Edition, where our very own Andrea Gustavson talks about her work teaching undergraduates in the archive.

Here's a taste of Gustavson's article:

Here's a taste of Gustavson's article:

In the fall, I taught a class called "American Images: Photography, Literature, Archive" that made extensive use of the collections at the Ransom Center. Each week, the students and I explored the intersections between photography, literature, and archival theory using the Center's primary materials as the foundation for our discussions. On Mondays and Wednesdays we met to discuss the week's reading, closely reading passages or images and making connections to contemporary events. On Fridays the students had the opportunity to view rare manuscripts and photographs that illustrated, extended, and even challenged many of the concepts we had discussed earlier in the week. Over the course of the semester, the students worked within a variety of written genres as they built toward a final project for which they conducted their own original research.

Check out the full article here.Gustavson is a PhD candidate in American Studies here at UT and she worked as a graduate intern in Public Services and as a Graduate Research Assistant at the Ransom Center in 2010–2014.

Faculty and Grad Research: Dr. Steve Hoelscher and Andi Gustavson on the Magnum Archive

Today we bring you a lovely piece hosted on the UT History Department's Not Even Past website: Dr. Steve Hoelscher and Ph.D. candidate Andi Gustavson have teamed up to bring you this piece on the Magnum archive of photography. We've reprinted an excerpt below; take a look at the full article here.

Today we bring you a lovely piece hosted on the UT History Department's Not Even Past website: Dr. Steve Hoelscher and Ph.D. candidate Andi Gustavson have teamed up to bring you this piece on the Magnum archive of photography. We've reprinted an excerpt below; take a look at the full article here.

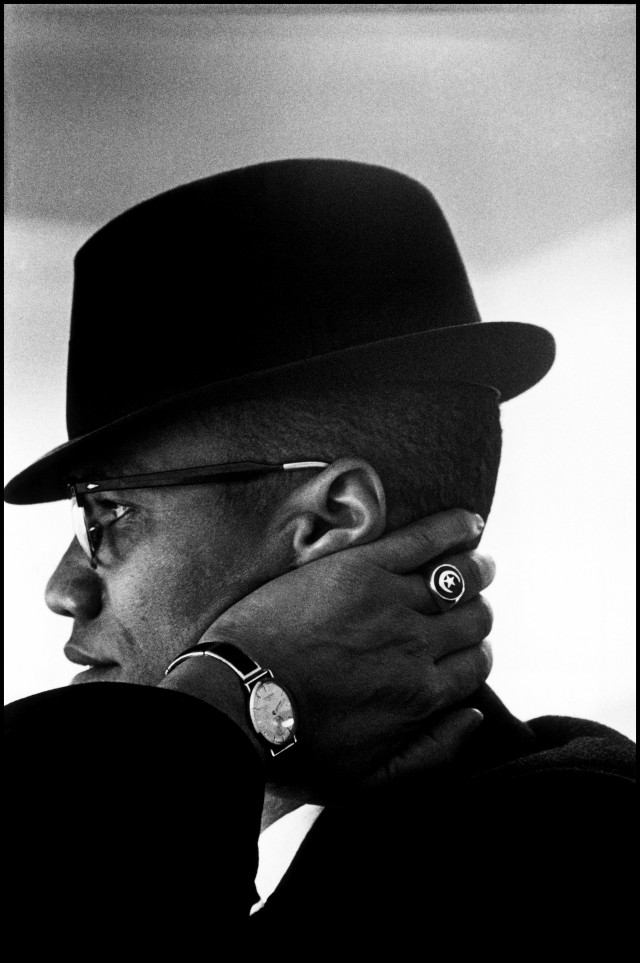

Like the print itself, the collection of photographs to which it belongs is now also retired—at least from its previous occupation of carrying the image it bears to publishing venues. Davidson’s print came out of retirement in the summer of 2010—or, more accurately, it took on a new life—when the Magnum Photo New York Print Library was opened for research at the Harry Ransom Center, a research library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin. The Magnum Photos collection, as it is now known, is comprised of some 1,300 boxes containing more than 200,000 press prints and exhibition photographs by some of the twentieth century’s most famous photographers. Once Magnum began using digital distribution methods for its photographs, the function of press prints as vehicles for conveying the image became obsolete and these photographs became significant solely as objects for both monetary and historic value.Magnum’s visual archive is a vast, living chronicle of the people, places, and events of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Images of cultural icons, from James Dean and Marilyn Monroe,to Gandhi and Castro, coexist in the Magnum Photos collection with depictions of international conflicts, political unrest, and cultural life. Included are famous war photos from the Spanish Civil War and D-Day landings to wars in Central America, Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as unforgettable scenes of historic events: the rise of democracy in India, the Chinese military suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, the U.S. Civil Rights movement, the Iranian revolution, and the September 11 terrorist attacks.

Announcement: AMS Graduate Conference this week: "Home/Sick"

Join the graduate students of the Department of American Studies at UT as they put on a conference that takes on the theme "Home/Sick" this Thursday and Friday, April 2 and 3. The keynote address will be delivered by Dr. Kim Tallbear (Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, UT Austin) on Thursday, April 2nd at 6pm in NOA 1.124. Dr. Tallbear will give a talk called, "Molecular Death and Redface Reincarnation: Indigenous Appropriations in the U.S." Panels will take place Thursday and Friday in the Texas Union. See below for a full schedule, or click here. The following is a description of the conference theme from the organizers:

The following is a description of the conference theme from the organizers:

The death of eighteen-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri this August, the immigration crisis centering around the influx of children from Central America to the United States, and the recent panic over the spread of the ebola virus can all be read as the newest manifestations of a long-running pattern throughout American history and culture: the relationship between constructions of “healthy” communities, the fear that these communities will be violated, invaded, or contaminated, and the mobilization of these fears as justification for action in the name of community preservation. The history of the United States is littered with rhetorical constructions of safety and security, purity and contamination—as well as with the results of very real processes of violence, displacement, and exclusion. The 2015 AMS Graduate Student Conference considers constructions of home and health, and explores how these concepts have been and continue to be mobilized in the construction and erasure of American communities, families, and selves.

Schedule for PanelsThursday, April 2Registration 1pm- 5pmSinclair Suite (UNB 3.128), Texas Union2:00pm - 3:30pm - Panel 1: Surveillance at HomeTexas Governors' Room (UNB 3.116), Texas Union3:45pm - 5:15pm - Panel 2: Sick: Bodies and AffectTexas Governors' Room (UNB 3.116), Texas UnionFriday, April 3Registration 8:30am - 5:00pmEastwoods Room (UNB 2.102), Texas Union9:00am - 10:30am - Panel 3: Race and Reconfiguring the HomeChicano Culture Room (4.206), Texas Union10:45 - 12:15 - Panel 4: Home in Digital LifeChicano Culture Room (4.206), Texas Union1:45 - 3:15 - Panel 5: Leisure, Labor, and Contested HomesChicano Culture Room (4.206), Texas Union3:30 - 5:00 - Panel 6: Gulf Coast Oil and the Labor of Self, Loss, and the SouthChicano Culture Room (4.206), Texas Union