Women and the Prison System

Madison was a student in AMS311s Prison Art, Literature, and Protest this summer! This research comes from her final project.

Part 1: An Outside Look at Women and the Prison System

Carceral feminism is the idea that “increasing policing, prosecution, and imprisonment” is the solution to reducing violence against women. Some examples of the implementation of carceral feminism into US law include the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity and Reconciliation Act. VAWA was a federal law signed by Bill Clinton in 1994, which attempted to reduce domestic violence by increasing police responsiveness to domestic violence calls and increasing sentencing for abusers. However, not long after, Clinton passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity and Reconciliation Act in 1996, which reformed VAWA. This reform placed a five-year limit on welfare, required recipients to work after two years, and placed a lifetime ban on welfare for anyone who was convicted of a drug felony, violated probation, or violated parole (whether the convictions were valid). As a result, many, especially women of color, were ineligible for welfare, and had no means of escaping their abusive relationships, making VAWA otherwise useless and ineffective at fulfilling its intended purpose. (Law 2014)

Aside from the reform, there are many other issues with carceral feminism. To begin with, it fails to acknowledge that police are often instigators of violence. An example of this is the case of Cherie Williams. She was a 35-year-old African American woman who attempted to call the cops to report domestic violence. However, instead of responding to the call and arresting the abuser, the officers arrested and committed violence against her, even threatening to harm her in the future. In addition, carceral feminism fails to acknowledge the ineffectiveness of the criminal justice system. Many victims who take their cases to court are often dismissed, invalidated, or blamed. The criminal justice system is controlled by men, and thus controlled by misogyny and ignorance of the needs and struggles of women. Additionally, carceral feminism fails to take into account the role of race, gender identity, immigration status, and social and economic inequities. As stated by Law, “Women marginalized by their identities, such as queers, immigrants, women of color, trans women, or even women who are perceived as loud or aggressive, often do not fit preconceived notions of abuse victims and are thus arrested.” (Law 2014)

Moreover, even if officers respond to the calls properly, incarceration rates of abusers are very low, with only 5 out of 1000 reported cases leading to incarceration. (Fulcher-Melendy 2021) Despite there being a great push to persuade women to report rapes to the police, the majority of rapes and sexual assaults go unreported because contrary to the beliefs proposed by carceral feminism, most victims do not want the incarceration of their assailant; they just want the violence to end.

For those in favor of carceral feminism, some questions to ask are: “Is incarceration justice for a sexual assaulter/domestic abuser/rapist? Do they learn, reflect, or feel guilty for what they’ve done? Does it provide closure for the victim? Does it help the victim heal?” As stated frankly by Fulcher-Melendy, “Prisons themselves are incapable of changing rapists.” (2011, pp. 11) In fact, rather than encouraging assailants to reflect on their violent actions, and seek to reform themselves, “male sex roles, violence, and power relations which lead to rape in the first place, are strongly reinforced within prison.” (Fulcher-Melendy, 2011, pp.11) In other words, carceral feminism is ineffective. And even worse, it diverts attention and resources away from real solutions. This includes programs that assist survivors in escaping abusive relationships by providing shelter, public housing, and welfare, community interventions, and long-term organizing. (Law 2014) These alternative solutions will be discussed later in Part 3 of this paper.

Part 2: An Inside Look of Women and the Prison System

Carceral feminism fails to effectively protect and support victims of domestic violence, and as a consequence, many women have been incarcerated for acts that were a means for their, and often their children’s, protection and survival. An example is the case of Marissa Alexander, a mother in Florida, who was routinely abused by her husband. During one incident, she fired a warning shot to protect herself from her husband. Instead of the police arresting the husband on accounts of domestic abuse, or providing Alexander with the resources she needed to leave her husband and find a safe place, she was arrested and prosecuted for aggravated assault. Alexander is not the only victim “forced to endure additional assault by the legal system.” In 2013, 67% of women sent to prison in the state of New York for murder were abused by that person; 93% in California. And in the past decades, the number of incarcerated women has continued to increase. (Law 2014)

Both within the legal system and inside the prison themselves, women are subject to a double standard. As stated by Davis, “There has always been a tendency to regard those women who have been publicly punished by the state for their misbehaviors as significantly more aberrant and far more threatening to society than their numerous male counterparts.” (Davis, 2011, pp. 66) As a result, women often receive longer sentences, with the justification that while men are there for punishment, women are there to be “reformed and retrained, a process that…required time.” (Davis, 2011, pp. 72) Additionally, longer sentences for women were supported by the belief that “genetically inferior” women needed to be “removed from society for as many of their childbearing years as possible.” In addition to longer sentences, while men are treated as criminals, women are treated as insane. As a result, a significantly greater proportion of women are sent to psychiatric institutions and prescribed psychiatric drugs.

Despite this view that incarcerated women are more threatening, the struggles of incarcerated women are often overlooked, as they only constitute a minor proportion of the incarcerated population. WIthin the prison itself, there are no arrangements made to accommodate sentenced women, their needs often neglected. In Davis’ book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, she cited an excerpt from Shakur’s autobiography that accurately describes the treatment of incarcerated women:

“‘...confined in a men’s prison, under twenty-four surveillance of her most intimate functions, without intellectual sustenance, adequate medical attention, and exercise, and without the company of other women…” (2011, pp.62)

Furthermore, some would think that incarceration meant safety for these women. Salvation from the abuse and violence they experienced in their day to day lives from their partners. On the contrary, those who “escape” domestic violence by incarceration, only become greater victims to state violence. Prisoners’ daily lives consist of routine strip searches and “internal examination of body cavities”. Pat-frisk or room searches where they are groped or touched inappropriately. Sexual violence, rape, verbal degradation, and harassment. Those with authority abuse their power and try to lure female prisoners to engage in sex by offering or denying goods. Those who refuse or attempt to oppose authority are threatened with force, violence, and sometimes even solitary confinement, until they concede. As described by the 1996 Human Rights Watch report, “...prison is a space in which the threat of sexualized violence that looms in the larger society is effectively sanctioned as a routine aspect of the landscape of punishment behind prison walls.” (Davis, 2011, pp.78) Similarly, in LeFlouria’s book Chained in Silence, she describes the prison environment as “...incessantly tormented by physical violence and rape” with “sexual predators that sometimes invaded the women’s quarters.” (2015, pp. 38-39)

Despite the horrid treatment and violation of women’s bodies and rights, those guilty of committing these actions rarely show remorse. Some justified their actions by stating that “women prisoners had rare opportunities for ‘male contact’” and therefore “welcomed” these actions. Others believed they could continue because they would not be held accountable or face any consequences. And some were not even aware of the wrong in their actions until a group of women reenacted the strip search that is so commonly performed on women in prisons. Many of the prison guards in the audience denied what they saw before them, in shock that that was how their actions were perceived. That’s when the reality hit that “without the uniform, without the power of the state [the strip search] would be sexual assault.” (Davis, 2011, pp. 83)

The mistreatment of women is magnified for women of color, especially Black women. In the past, Black women were often segregated from White women, disproportionately sentenced to men’s prisons, and received forms of punishment that overlooked their gender. In addition to this, they are deprived of proper medical treatment and overall care for their well being. A great illustration of this occurrence is described in Shakur’s autobiography. In it, she describes how her doctor refused to confirm her pregnancy, instead advocating that she had an “intestinal disorder”. Later, when she was having complications with her pregnancy, he insisted she receive an abortion saying “it will be better for you and for everyone else.’” (Shakur, 2016, pp. 126) This mistreatment wasn’t limited to the prison doctor, but included everyone in the prison system. Many attempted to prevent Dr. Garrett, a proper doctor who cared for Shakur’s well-being, from treating her. In some other incidents, she was left “anemic and malnourished” and “left in a room for three days with a woman who turned out later to have active tuberculosis.” (Shakur, 2016, pp. 141-142)

Not only were Black women, like Shakur, deprived of proper medical treatment, but they were also victims of racial violence. They were disproportionately subject to be kept in solitary confinement and psych wards. If they refused orders, they were jumped and beaten. This racial violence was evident in these depictions made by Shakur, describing her experience during pregnancy:

“...a million police cars buzzing around the vehicle in which I, a woman in labor, was riding.”

“They put me in an ambulance, chained me to a stretcher, and brought me back to the Women’s House of Detention at Rikers Island.” pg 144

“My mental stability was also threatened by the round-the-clock guards who sat outside my hospital room with shotguns trained at my head.” pg 141

(2015, pp.141-144)

The worst and most prominent form of this violence was sexual violence. The sexual violence that was commonly experienced by female prisoners was heightened for women of color, as preexisting images of hypersexuality and promiscuity in these women “justified” many of the sexual assaults committed against them. (Davis, 2011, pp. 80) Much of the sentiment that existed during slavery carried over to the prison system, with many guards believeing that they “owned” the right of sexual access to Black women. As a result, many were exempt from legal punishment for raping Black women prisoners. (LeFlouria, 2015, pp. 40-41)

Part 3: Consequences and Alternative Solutions

One of the largest consequences of the prison system is the toll it takes on women’s physical, mental, and emotional health, with the largest contributing factor being the sexual violence they experienced daily. During their time in the prison, and even when they leave, many women experience anxiety, fear, and depression. Some experience insomnia or hypersomnia, PTSD, social withdrawal, low self-esteem, and feelings of guilt and worthlessness. Many develop sexual dysfunction or avoid sexual intercourse due to loss of sexual satisfaction. This sometimes even manifested into avoiding marriage or intimacy with another person all together. (LeFlouria, 2015, pp. 42-43)

As discussed in Part 1, carceral feminism is essentially ineffective at protecting women from sexual violence, or connecting them to the resources needed to support their escape from it. So, what can be done instead of relying on carceral feminism and reporting abusers to the criminal justice system?

One alternative largely advocated by the writers in the Letter to the Anti-Rape Movement is the confrontation of the assailant. What this entails is holding the assailant accountable for their actions and making them responsible for making a change. This is especially important because in the majority of rape and sexual assault cases, victims often blame themselves for what happened. This may have been because of manipulation from the assailant or ideas upheld in society. Thus, it is important that they hold the assailant responsible for their actions and not themselves. In addition, this may be more effective than reporting the assailant. As stated in the letter, by using the criminal justice system, a woman takes on a passive role, where decisions are made for her. By confronting her assailant, she has the power and autonomy to receive the closure and healing she needs. (Fulcher-Melendy, 2021, pp. 12)

This idea of confronting the assailant is greatly demonstrated by “Goldflower’s Story”. This story speaks about a woman who was being routinely abused by her husband and father-in-law. Seeking help, she sought out the women’s association in her local village. She shared her sufferings with the women, and united they sought out her abusers. They tied them up and beat them up until they promised to reform themselves. Some did choose reform, others did not. However, those who chose to continue to abuse these women, were soon confronted again by the women’s association. (Sloan, 2005)

Although the above example is a bit extreme, it promotes the idea that when women build a reliable community, they can come together and challenge the existence of sexual violence. A modern example of this community is evident in the creation of the website Creative Interventions. Creative Interventions is a website that was designed by an anti-violence advocate, Mimi Kim, to offer tools and resources to the public to help address sexual violence. A notable feature of the website is the collection of peoples’s stories and experiences with sexual violence that fosters a community so others know they are not alone.

Closing Remarks

In summation, carceral feminism has many shortcomings that fail to provide women the support and protection they need from domestic violence. A consequence of this failure is the incarceration of many women who were simply trying to escape this violence. As a result, they then become trapped in the prison system, where domestic violence is replaced by state violence. The effect of both forms of violence take a large toll on women’s physical, mental, and emotional health. There are many alternative solutions to dealing with sexual violence and recovering from its effects. This includes confronting the assailant, rather than reporting them, and developing and relying on a community of women to both confront the problem and heal from it.

Sources:

Davis, A. Y. (2011). How Gender Structure the Prison System. Are prisons obsolete? (pp. 60-83) Seven Stories Press.

Davis, A., & Shakur, A. (2016). Assata: An autobiography. Zed Books.

Fulcher-Melendy, D., & Fulcher-Melendy, D. (2021, December 13). Open Letter to the Anti-Rape Movement. The Feminist Poetry Movement. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://sites.williams.edu/engl113-f18/fulcher-melendy/an-open-letter-to-the-anti-rape-movement/

Kim, M. (n.d.). Creative interventions. creative interventions. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.creative-interventions.org/

Law, V., Law, V., Oduor, J.-B., Nelson, S., Watt, F., Gill, T., Chomsky, N., Marcetic, B., Elrod, A., Shaw, D., Finn, D., Pagliarini, A., Sirota, D., Marx, P., Becker, J., Stetler, H., Jamie Allinson Asli Bali Allison McManus, Allinson, J., Bali, A., … Featherstone, L. (n.d.). Against Carceral Feminism. Jacobin. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://jacobin.com/2014/10/against-carceral-feminism/

Sloan, S. (2005, March 1). Socialist Revolution and Women's Liberation. Liberation News. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.liberationnews.org/05-03-01-socialist-revolution-womens-lib-html/

Prison Murals and Transgender Activism

Elizabeth Nguyen was a student in AMS311s

My painting takes place in a prison that incorporates the Arts-in-Corrections program, and the specific scene is the mural photography center. This is depicted by the 2 murals, a table with paint equipment, a camera, and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) reference. The painting I produced relates to transgender activism and the art of the incarcerated. I created a painting because I was interested in applying my own interpretation of what a prison mural could look like. This form of art resonates with me because painting offers me an escape from reality which can be a helpful coping mechanism at times. Paintings can also embody a variety of different meanings which allows individuals to relate to the piece in their own personal way. In addition, viewing a painting can cause us to forget for a moment the background of the painter and appreciate their art. Viewing a painting or painting may provide the feeling of escape for the incarcerated by allowing them to feel and imagine the mural’s image as their current environment for some time.

In some prisons, the incarcerated individuals have the opportunity to create art, like painting wall murals. These murals are used as a photography backdrop for group and individual photos. The images cost approximately $2.00-$3.00 each. In addition, the prison photographer position is rotated amongst the incarcerated (Fleetwood 492). Some prison murals reference iconic landmarks however, the majority of the murals do not specify a location because the focus is on painting a place that has a light, is ungoverned, and has a few boundaries. It is also common to not see symbols that represent human life or a built environment. However, if these symbols are present, it’s typically depicted as a lighthouse or farmhouse. A reason for the vague mural paintings is to increase the difficulty of hiding gang signs (496-497). I incorporated a lighthouse in my painting to represent the built environment, a sunset to symbolize light, and a beach landscape to reflect a place with few borders.

A partnership between the CDCR and the California Arts Council led to the creation of the Arts-in-Corrections program which focuses on introducing the incarcerated to different forms of art such as painting, dancing, and music to inspire change and creativity and prevent recidivism. This program reduced institutional violence and improved self-discipline in the San Quentin State Prison (Linn). The Trans People Exist in the Future is a composition of selected visual images and poems from the Trans Day of Resilience art project (“Trans People Exist in the Future” 1). Butterflies were a common theme in 2 of the images (8, 24). A butterfly represents the transformation of a transgender individual. A caterpillar transitions into a butterfly and the individual transitions into a gender identity that differs from their sex at birth. In my painting, butterflies are escaping from an open mason jar which reflects an individual embracing their desired gender identity with the world.

There are prisons that are not in solidarity with and do not respect an incarcerated individual’s LGBTQ+ identity. This can cause the individual to live in a violent and mistreated living environment which can create a “painful void”(O’Donnell). There has also been an overwhelmingly large number of incarcerated transgender women being transferred into men's prisons or solitary confinement. Although the United Nations (UN) considers solitary confinement for more than 15 consecutive days as torture, many transgender individuals stay past this standard. These individuals even those without nonviolent offenses are often housed in solitary confinement for their own “protection”. In solitary confinement, they are deprived of accessing rehab, early release programs, warm living conditions, educational opportunities, and more (Ophelian). Therefore, it is important for incarcerated transgender individuals to understand that they are not alone in fighting for humane treatment and visibility. This can be achieved by conversing with the incarcerated individuals about shared experiences and offering support (O’Donnell). This act of showing support for the incarcerated, especially the transgender individuals, is present in the mural depicting Miss Major, with a backdrop of the transgender, and an inspiring quote. Miss Major is a trans woman activist and has been advocating for transgender women of color rights for more than 40 years. She is viewed as a mother, father, and grandparent by many and has been described as a safety net along with being a sage individual. She served as the first executive director of the Transgender Gender-Variant & Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP) which offers legal services for formerly or currently incarcerated transgender individuals (Ophelian). Miss Major was also incarcerated for four years. When Miss Major was asked about the advice she would share with the transgender individuals, she responded, “You have to keep the faith and keep going...” (Diavolo). The quote emphasizes perseverance and having it be said by a person who was formerly incarcerated and who still remains committed to helping the incarcerated transgender individuals makes the connection between her and the incarcerated more meaningful. Painting this specific mural was my way of conversing with and expressing my faith in the incarcerated transgender individuals.

Works Cited

Diavolo, Lucy. “Miss Major Griffin-Gracy Is Still Here and Wants Young Activists to

“Keep on Fighting”.” Teen Vogue, Condé Nast, 17 Jun. 2020, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/miss-major-griffin-gracy-still-here-young-activists-keep-fighting. Accessed 4 July 2022.

Fleetwood, Nicole R. “Posing in Prison: Family Photographs, Emotional Labor, and Carceral Intimacy.” Public Culture, vol 27, no. 3 (77), 1 Sept. 2015, pp. 487–511. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2896195. Accessed 4 July 2022.

Linn, Sarah. “Arts-in-Corrections: California's Creative Response to a Broken Prison System.” KCET, Public Media Group of Southern California, 12 Aug. 2016, https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/arts-in-corrections-californias-creative-response-to-a-broke n-prison-system. Accessed 4 July 2022.

Major! Directed by Annalise Ophelian, performance by Miss Major Griffin Gracy, Floating Ophelia Productions, 2015. Accessed 4 July 2022.

O’Donnell, Kimberley. “The radical importance of writing letters to trans people in prison.” DAZED, 12 Feb. 2019, https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/43209/1/trans-lgbtq-people-prison-writing-lette rs-volunteer-activism. Accessed 4 July 2022.

“Trans People Exist In The Future.” Trans Day of Resilience, Forward Together, Nov. 2020, tdor.co/art/trans-people-exist-in-the-future-zine. Accessed 4 July 2022.

Please join us in celebrating the wonderful Coyote Shook's most recent publications!

Shook’s publications are as follows—

The Gospel According to Sister Wendy with Moon City Review (hard copy only) & 5 Variations on Submissions to the Texas Right to Life Heartbeat Act Anonymous Tip Form with The Hunger Mountain Review.

Whitney S. May’s newest publication in Ampersand: An American Studies Journal

Check out Whitney S. May's newest publication in Ampersand: An American Studies Journal "Bearing the Palls of Shopping Malls: Necropsying (Dead) Mall Nostalgia in Netflix's Fear Street Trilogy! Just in time for the start of SPOOKY SEASON. You can read it here: Bearing the Palls of Shopping Malls

Social Media team update! Welcome Amanda Lee Tovar

Hi! I am Amanda, but most people call me Mandee—which I prefer! I am officially a third year in the PhD program in American Studies.

I’m really excited to be taking on the role of social media for the AMS Program this year. I like to think of myself as the “ultimate consumer of content” since I am constantly tapped in to social. Hopefully in all of that I can do this role justice and provide great content to represent, promote and celebrate our program, but more importantly YOU!!!

To that I definitely need your help! Please feel free to send me ANY and ALL updates about your accomplishments, your life within and outside of AMS, and of course about the program. I would also like to know about our students, and upcoming events. I really want to get them featured here and distributed in an engaging way. I welcome any and all content leads that can help our program thrive.

That’s all for now! It’s now time for me to paint my office! ❤️✨

“Deeply Rooted in the Nation’s History and Tradition”:Nativism, Sexism, and Criminalization in 19th and 21st Century America

Jessica Suess is a undergraduate majoring in American Studies and History with a minor in Women and Gender Studies. She is particularly interested in feminist movements and the experiences of working class women in the United States. This paper was written for AMS 311S: Prison Art, Literature, and Protest.

“Guided by the history and tradition that map the essential components of the Nation’s concept of ordered liberty, the Court finds the Fourteenth Amendment clearly does not protect the right to an abortion.… By the time the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, three-quarters of the States had made abortion a crime at any stage of pregnancy.” - Samuel Alito, Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health

In Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health, a majority consisting solely of the Supreme Court’s conservative justices overturned Roe v Wade and thereby eliminated the federal guarantee of the right to control one’s reproduction, relegating that decision to each state individually. Samuel Alito, writing for the majority, grounds his reasoning in originalism, the idea that the deciding factor in judicial thinking should be the framers’ state of mind, and specifically in the understanding of a woman’s rights possessed by the ratifiers of the 14th Amendment in 1868. Because those mid-nineteenth century men and their predecessors did not conceive of reproductive rights as fundamental, Alito concludes that the right to terminate a pregnancy is not “deeply rooted in the nation’s history and traditions”, a phrase which appears in various forms throughout the document. He recognizes but finds no legal significance in the motivations behind the nineteenth century anti-abortion laws the decision hinges on. However, the nativist and sexist animus behind the advocacy for those laws is historically significant, as these ideas are, in fact, “deeply rooted” and their iterations continue to permeate American society over 150 years later, finding expression in the modern carceral institutions that – with the protection of Roe removed – more pregnant Americans will find themselves targeted by.

The state laws prohibiting abortion in existence in 1868 were motivated by a nativist desire to limit the freedom of Anglo-Saxon mothers to control their pregnancy and therefore prevent a dilution of Anglo-Saxon demographic power by immigrants, largely Irish Catholic, who were assumed to possess a criminal nature and were therefore unsuitable for American public life. Alito briefly acknowledges these motivations in Dobbs vs Jackson Women’s Health, however he minimizes them as merely “the fear that Catholic immigrants were having more babies than Protestants” and asserts that the basis of that understanding is confined to a single source[1]. In their paper, “Abortion, Race, and Gender in Nineteenth-Century America”, Nicola Biesel and Tamara Kay evaluated a multitude of sources, finding that “physicians made overt appeals to the racial interests of Anglo-Saxons when they argued that abortion should be prohibited to ensure Anglo-Saxon political control and preserve Anglo-Saxon civilization” and therefore that objection to abortion stemmed not only from nineteenth century understandings of a woman’s role in society, but from nativist ideas of who should be considered American[2].

Figure 1: Abortion Laws per US State by Year Adopted, data from Appendix A of Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health (territories in orange)

Of the laws cited by the majority opinion and in place in 1868, 79% were passed after 1845, a period corresponding to increased immigration and growing nativist sentiment[3]. Prior to 1845, 10,000 to 100,000 people immigrated to the U.S. annually, but 2.9 million arrived between 1845 and 1854[4]. In 1850, foreign-born individuals comprised 11.48% of the white population which increased to 15.37% ten years later[5]. Nativist sentiment, measured by interest in associated political organizations, increased in the same period. The Order of United Americans (OUA) which would become the Know Nothings – the first political party to include immigration concerns as a major part of their platform[6] -- boasted 2000 members at the end of 1846, but up to 30,000 nationally by 1851 and 30,000 in the state of New York alone by 1855[7].

Thomas Whitney – a founding member of OUA and “its most serious theorist and prolific propagandist”[8] – wrote in 1856 that people “are entitled to just such privileges, social and political, as they are capable of employing and enjoying rationally”[9]. Immigrants, particularly Irish Catholics, were characterized as lazy, dishonest, drunk, and criminal, and therefore unfit citizens[10]. The nativists feared that the “foreign” values and presumed criminal nature of immigrants would lead to the deterioration of American society[11]. The criminalization of immigrants had a predictable effect on their rates of incarceration. In 1850, immigrants constituted 9.7% of the total (including non-white) population, but 35.8% of prisoners which, in 1860, increased to 13.2% of the total population and 46.9% of prisoners[12]. The vote, however, was of primary concern as Anglo-Saxon political power in the northern states depended on electoral success[13]. Accordingly, the Know Nothings favored a waiting period of 21 years between naturalization and suffrage[14].

Figure 2 Caricatures of Irish and German Immigrants steal a ballot box, 1850s. "Nativism and the Know-Nothing Party: American Art in Context," in Smarthistory, February 26, 2021, accessed July 4, 2022

Though the outbreak of the Civil War temporarily pushed immigration concerns to the background, nativist sentiment did not disappear, and is in fact alive and well in the 21st century United States in the form of the “great replacement” theory. Like the nativism espoused by Whitney and the Know Nothings, the “great replacement” theory “insists that entire categories of human beings can or should be excluded from democratic rights and protections” and holds that the conservative, white vote is in danger of being overwhelmed -- in the words of Fox News host Tucker Carlson -- by “more obedient voters from the Third World” welcomed by Democrats to dilute Republican electoral power[15]. A recent Southern Poverty Law Center poll found that almost 70% of surveyed Republicans agreed to at least some extent with white nativist ideas that “that demographic changes in the United States are deliberately driven by liberal and progressive politicians attempting to gain political power by ‘replacing more conservative white voters’”[16].

In this period of heightened concern at the presence of immigrants and the threat they supposedly present to American society, the focus has shifted away from Europe and toward Central and South America and “the perception of Latinos as inherently foreign to the very image and idea of ‘being an American’’ has now become deeply ingrained”[17]. Studies of immigrant representation in news media find that “the most dominant negative characterizations… focus on their perceived criminal tendencies”[18]. Accordingly, rates of incarceration for immigrants are increasing – an average daily population of 34,000 in 2016 rose to 42,000 two years later[19] -- and just like foreign-born Americans in the nineteenth century, Hispanic citizens are imprisoned at rates at odds with their share of the population: 16% of the U.S. population in 2010, but 19% of prisoners[20].

Troublingly, recent whistleblower allegations assert that migrant women held in an I.C.E. detention in Georgia have been sterilized without their informed consent[21]. As of November 19, 2020, 57 women have reported either undergoing unnecessary surgery at the center or being pressured to, and that is likely an undercount due to the deportation of witnesses and survivors and other factors[22]. Forced sterilization of minorities, the poor and those with intellectual disabilities has a long and shameful history in the United States[23]. It reflects the presumption that the state has the right to control its demographic makeup by eliminating the reproductive capacity of potential parents considered to be “unfit”. Though the technology did not exist at the time – the first female surgical sterilization was performed in 1880[24] – it is an intervention mid-nineteenth century nativists would have lauded.

In 1868 -- when Alito would like to source our understanding of reproductive rights -- the role of a woman was understood to be that of a wife and mother. He acknowledges that, in addition to concerns regarding the relative fertility of Catholic immigrants, the motivation behind the mid-nineteenth century anti-abortion laws included fears that “the availability of abortion was leading White Protestant women to ‘shir[k their] maternal duties’”[25]. The physicians advocating for these laws “argued that it was the obligation of Anglo-Saxon women to reproduce the race and thus the nation” and opposed both abortion and contraception on the grounds that control of one’s reproduction contravened a woman’s purpose[26]. Alito notes that when nineteenth century legislatures prohibited abortion, the right to which allows a woman to participate fully in the public sphere, no one objected that “the laws… violated a fundamental right”[27]. However, women were not understood to have a right to equal participation in society. The only suitable public roles for a woman were those “deemed extensions of their maternal and moral roles within the home”[28].

The idea that a woman subverts her natural obligation by terminating her pregnancy is not a relic of the nineteenth century. Though most anti-choice organizations maintain disciplined messaging and avoid hostility toward the person in possession of a uterus, even a cursory survey of the popular Reddit forum’s “pro-life” section reveals plentiful examples of an abortion seeker being derided as selfish for their choice[29]. As Noam Shpancer notes in his essay “Women and Selfishness”: “the association between femaleness and nurturing, caring and consideration permeates our culture”[30]. A woman who prioritizes her own needs or desires rather than the potential life promised by an embryo is therefore violating cultural expectations of self-sacrificing femininity.

Lynn Paltrow and Jeanne Flavin’s examination of cases “in which a woman’s pregnancy was a necessary factor leading to attempted and actual deprivations of [their] liberty” demonstrates that those expectations already contribute to the criminalization of expectant parents[31]. Most of those cases involved an accusation of drug use and, crucially, in fully 64% there was no adverse outcome to the pregnancy[32]. In one example, a woman who sought help for her drug use during her pregnancy was confined to a psychiatric hospital against her will, where she received no prenatal care, and once released was surveilled by the state for the remainder of her pregnancy, despite a doctor’s testimony that her drug use did not endanger the fetus[33]. She suffered confinement and then state supervision for months, losing her job as a result, because as a drug-user she did not meet the cultural expectations of motherhood. This study examined 413 such cases between 1973 and 2005, but National Advocates for Pregnant Women has identified 1,331 additional cases from 2006 to 2020 – after the introduction of fetal personhood bills in many states[34].

Unsurprisingly, most of the women represented in Paltrow and Flavin’s study (52%) were Black. In the U.S., “race has always played a central role in constructing perceptions of criminality”[35]. Like nativism and the primacy of maternity in cultural conceptions of a woman’s role, racialized criminalization of Black citizens is “deeply rooted” in our history. Though Black Codes, which proscribed such malicious acts as vagrancy – provided the perpetrator was Black – were ostensibly eliminated by the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment two years later, similar laws remained on the books for decades[36]. The contemporary mass incarceration crisis, which disproportionately deprives Black Americans of their liberty, is but “one historical moment within a much longer and larger antiblack punitive tradition”[37].

Anti-Black racism was not a significant factor in mid-nineteenth century nativism. During the antebellum heyday of the Know Nothing party, most Black Americans were cruelly enslaved and possessed no rights at all nor any conceivable route to displace white Anglo-Saxon political power in the north. The white supremacist ideas that justified the institution of chattel slavery in the United States and then the glorification of the confederacy are however a feature of that nativism’s modern iteration[38]. The “great replacement” narrative is believed to be a motivation behind the murder of ten people, most of them Black, at the Tops Supermarket in Buffalo, New York in May. Nativist ideas fill the document allegedly posted online by the shooter[39]. A nineteenth century fear of Catholic fertility has now morphed into a white supremacist nativism which has already incited terrible violence.

These traditions – sexist ideas of a woman’s role in society as well as nativism and the white supremacy entangled within it – are “deeply rooted” in our nation’s history. Alito and the five concurring justices find no legal significance in the influence these insidious ideologies had on the passage of anti-abortion laws in the mid-nineteenth century. However, those ideas are still in operation today. Now that Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health has opened the cell door to the criminalization of people seeking to terminate their pregnancy, the burden of real or potential loss of liberty will fall disproportionately on non-white Americans. For an increasing number of women prosecuted for being pregnant but failing to live up to society’s expectation of motherhood, it already has.

BBC News. “ICE Whistleblower: Nurse Alleges ‘Hysterectomies on Immigrant Women in US,’” September 15, 2020, sec. US & Canada. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-54160638.

Bauder, David. “What Is ‘Great Replacement Theory’ and How Does It Fuel Racist Violence?” PBS NewsHour, May 16, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/what-is-great-replacement-theory-and-how-does-it-fuel-racist-violence.

Beisel, Nicola, and Tamara Kay. “Abortion, Race, and Gender in Nineteenth-Century America.” American Sociological Review 69, no. 4 (2004): 498–518.

Boissoneault, Lorraine. “How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics.” Smithsonian Magazine. January 26, 2017. Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/immigrants-conspiracies-and-secret-society-launched-american-nativism-180961915/.

Brown, Hana E., Jennifer A. Jones, and Andrea Becker. “The Racialization of Latino Immigrants in New Destinations: Criminality, Ascription, and Countermobilization.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 4, no. 5 (2018): 118–40. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2018.4.5.06.

Clark, Simon. “How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics.” Center for American Progress. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/white-supremacy-returned-mainstream-politics/.

Davis, Angela. Are Prisons Obsolete. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003.

Davis, Angela. Women, Race and Class. New York: Random House Inc, 1981

Epps, Garrett. “The Antebellum Political Background of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Law and Contemporary Problems 67, no. 3 (2004): 175–211.

Evans, Brenna. “The Long Scalpel of the Law: How United States Prisons Continue to Practice Eugenics Through Forced Sterilization.” Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality (blog), June 7, 2021. https://lawandinequality.org/2021/06/07/the-long-scalpel-of-the-law-how-united-states-prisons-continue-to-practice-eugenics-through-forced-sterilization/.

Frink, Sandra. “Women, the Family, and the Fate of the Nation in American Anti-Catholic Narratives, 1830-1860.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 18, no. 2 (2009): 237–64.

Hernández, César Cuauhtémoc García. “Abolish Immigration Prisons.” The New York Times, December 2, 2019, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/02/opinion/immigration-detention-prison.html.

Hinton, Elizabeth, and DeAnza Cook. “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview.” Annual Review of Criminology 4, no. 1 (January 13, 2021): 261–86. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-060520-033306.

Kavattur, Purvaja. “Arrests and Prosecutions of Pregnant Women, 1973-2020 - New York.” National Advocates for Pregnant Women, September 18, 2021. https://www.nationaladvocatesforpregnantwomen.org/arrests-and-prosecutions-of-pregnant-women-1973-2020/.

Lefouria, Tabitha. Chained in Silence. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Levine, Bruce. “Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery: Thomas R. Whitney and the Origins of the Know-Nothing Party.” The Journal of American History 88, no. 2 (2001): 455–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/2675102.

Oboler, Suzanne. “‘Viviendo En El Olvido’: Behind Bars, Latinos and Prison.” Latino Studies 6 (2008): 1–10.

Paltrow, Lynn M., and Jeanne Flavin. “Arrests of and Forced Interventions on Pregnant Women in the United States, 1973–2005: Implications for Women’s Legal Status and Public Health.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 38, no. 2 (April 1, 2013): 299–343. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-1966324.

Prison Policy Initiative. “Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census.” Accessed July 4, 2022. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/rates.html.

Ritter, Luke. Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis: Political Nativism in the Antebellum West. Fordham University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv119907b.8.

Serwer, Adam. “Conservatives Are Defending a Sanitized Version of ‘The Great Replacement.’” The Atlantic, May 18, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/05/buffalo-shooting-republican-great-replacement/629903/.

Shpancer, Noam. “Women and Selfishness.” Psychology Today. Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/insight-therapy/201110/women-and-selfishness.

Southern Poverty Law Center. “SPLC Poll Finds Substantial Support for ‘Great Replacement’ Theory and Other Hard-Right Ideas.” Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.splcenter.org/news/2022/06/01/poll-finds-support-great-replacement-hard-right-ideas.

Whittum, Michelle, Robyn Schickler, Nicole Fanarjian, Rachel Rapkin, and Brian T. Nguyen. “The History of Female Surgical Sterilization.” Journal of Gynecologic Surgery 37, no. 6 (December 2021): 459–64. https://doi.org/10.1089/gyn.2021.0101.

(Brief-Address-2474 ). “Getting this off my chest.” Reddit. June 30, 2022. https://www.reddit.com/r/prolife/comments/vo3cuc/getting_this_off_my_chest

(eternitypasses). “Why are you against abortion??” Reddit. Jun 28, 2022. https://www.reddit.com/r/prolife/comments/vn4qva/why_are_you_against_abortion/

(Kidsrgr8-h8parenting). “Prochoice people are selfish and only care about themselves.” Reddit. Jun 8, 2022. https://www.reddit.com/r/prolife/comments/v7j51j/prochoice_people_are_selfish_and_only_care_about/

[1] Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health, No 19-1392 (U.S. June 24, 2022), 28

[2] Nicola Beisel and Tamara Kay, “Abortion, Race, and Gender in Nineteenth-Century America,” American Sociological Review 69, no. 4 (2004): 499.

[3] Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health, No 19-1392 (U.S. June 24, 2022), 79-108; See also Figure 1.

[4] Lorraine Boissoneault, “How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 26, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/immigrants-conspiracies-and-secret-society-launched-american-nativism-180961915/.

[5] Luke Ritter, Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis: Political Nativism in the Antebellum West (Fordham University Press, 2021), 107, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv119907b.8.

[6] Boissoneault, “Know Nothing Party”

[7] Ritter, Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis, 106-107

[8] Bruce Levine, “Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery: Thomas R. Whitney and the Origins of the Know-Nothing Party,” The Journal of American History 88, no. 2 (2001): 461, https://doi.org/10.2307/2675102.

[9] Levine, “Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery”, 465

[10] Boissoneault, “Know Nothing Party”; Levine, “Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery”, 469

[11] Ritter, Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis, 105

[12] Ritter, Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis, 107

[13] Beisel and Kay, “Abortion, Race, and Gender”, 499

[14] Levine, “Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery”, 470

[15] Adam Serwer, “Conservatives Are Defending a Sanitized Version of ‘The Great Replacement,” The Atlantic, May 18, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/05/buffalo-shooting-republican-great-replacement/629903/.

[16] Southern Poverty Law Center, “SPLC Poll Finds Substantial Support for ‘Great Replacement’ Theory and Other Hard-Right Ideas,” Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.splcenter.org/news/2022/06/01/poll-finds-support-great-replacement-hard-right-ideas.

[17] Suzanne Oboler, “‘Viviendo En El Olvido’: Behind Bars, Latinos and Prison,” Latino Studies 6 (2008): 3

[18] Hana E. Brown, Jennifer A. Jones, and Andrea Becker, “The Racialization of Latino Immigrants in New Destinations: Criminality, Ascription, and Countermobilization,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 4, no. 5 (2018): 119, https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2018.4.5.06.

[19] César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, “Abolish Immigration Prisons,” The New York Times, December 2, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/02/opinion/immigration-detention-prison.html.

[20] Prison Policy Initiative, “Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census,” accessed July 4, 2022, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/rates.html.

[21] “ICE Whistleblower: Nurse Alleges ‘Hysterectomies on Immigrant Women in US,’” BBC News, September 15, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-54160638.

[22] Brenna Evans, “The Long Scalpel of the Law: How United States Prisons Continue to Practice Eugenics Through Forced Sterilization,” Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality (blog), June 7, 2021, https://lawandinequality.org/2021/06/07/the-long-scalpel-of-the-law-how-united-states-prisons-continue-to-practice-eugenics-through-forced-sterilization/.

[23] Angela Davis, Women, Race and Class. (New York: Random House Inc, 1981), 216-220

[24] Michelle Whittum et al., “The History of Female Surgical Sterilization,” Journal of Gynecologic Surgery 37, no. 6 (December 2021): 459, https://doi.org/10.1089/gyn.2021.0101.

[25] Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health, 28

[26] Beisel and Kay, “Abortion, Race, and Gender”, 514; 506

[27] Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health, 28

[28] Sandra Frink, “Women, the Family, and the Fate of the Nation in American Anti-Catholic Narratives, 1830-1860,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 18, no. 2 (2009): 244.

[29] (Kidsrgr8-h8parenting), “Prochoice people are selfish and only care about themselves”, Reddit, Jun 8, 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/prolife/comments/v7j51j/prochoice_people_are_selfish_and_only_care_about/; (Brief-Address-2474 ), “Getting this off my chest”, Reddit, June 30, 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/prolife/comments/vo3cuc/getting_this_off_my_chest/: “it hurts me deeply to think that so many people would be so selfish to say its "my body" that they'd kill a baby out of what appears to me as ignorance”; (eternitypasses), “Why are you against abortion??”, Reddit, Jun 28, 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/prolife/comments/vn4qva/why_are_you_against_abortion/: “A woman’s convenience is more important than another human’s right to life? How do you square that one exactly?”

[30] Noam Shpancer, “Women and Selfishness,” Psychology Today, accessed June 26, 2022, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/insight-therapy/201110/women-and-selfishness.

[31] Lynn M. Paltrow and Jeanne Flavin, “Arrests of and Forced Interventions on Pregnant Women in the United States, 1973–2005: Implications for Women’s Legal Status and Public Health,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 38, no. 2 (April 1, 2013): 299, https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-1966324.

[32] Paltrow and Flavin, “Arrests of and Forced Interventions on Pregnant Women”, 333

[33] Paltrow and Flavin, “Arrests of and Forced Interventions on Pregnant Women”, 307-308

[34] Purvaja Kavattur, “Arrests and Prosecutions of Pregnant Women, 1973-2020 - New York,” National Advocates for Pregnant Women, September 18, 2021, https://www.nationaladvocatesforpregnantwomen.org/arrests-and-prosecutions-of-pregnant-women-1973-2020/.

[35] Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete, (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003), 28.

[36] Garrett Epps, “The Antebellum Political Background of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Law and Contemporary Problems 67, no. 3 (2004): 205; Elizabeth Hinton and DeAnza Cook, “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview,” Annual Review of Criminology 4, no. 1 (January 13, 2021): 267-268, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-060520-033306.; Tabitha Lefouria, Chained in Silence, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 58.

[37] Hinton and Cook, “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans”, 263

[38] Simon Clark, “How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics,” Center for American Progress (blog), accessed July 8, 2022, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/white-supremacy-returned-mainstream-politics/.

[39] David Bauder, “What Is ‘Great Replacement Theory’ and How Does It Fuel Racist Violence?,” PBS NewsHour, May 16, 2022, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/what-is-great-replacement-theory-and-how-does-it-fuel-racist-violence.

The Articles, Visual Art, Book chapters, and Films our Faculty and Grad Students Made!

The accomplishments of our faculty and grad students continue to amaze me, especially during a pandemic. From journal articles to visual art to documentary films, here is some of the amazing work done in the past year (ish!) All random commentary comes from me unless otherwise stated-Holly Genovese, Ph.D. Candidate in American Studies, Editor AMS: ATX.

Whitney May (Ph.D. Candidate in American Studies):

From Whitney “last year, my article “'Powers of Their Own Which Mere “Modernity" Cannot Kill’: The Doppelgänger and Temporal Modernist Terror in Dracula” was published in the journal Gothic Studies. My chapter “Topophilic Perversions: Spectral Blackface and Fetishizing Sites of Monstrosity in American Dark Tourism” was published in an edited collection called Religion, Culture, and the Monstrous: Of Gods and Monsters. (This was an extension of my term paper for Shirley Thompson’s 385 in fall, 2019.)

Later this semester, my chapter “The Way the Cookie Doubles: Cripping the Cyber-Gothic of Black Mirror’s AI Tech,” will appear in an edited collection called Humanity in a Black Mirror: Essays on Posthuman Fantasies in a Technological Near Future.” (This was my term paper for Alison Kafer’s Sick/Slow/Mad: Crip Theory course in spring, 2020.)”

And pre-order Whitney’s forthcoming edited collection! Encountering Pennywise: Critical Perspectives on Stephen King’s It, forthcoming from the University Press of Mississippi.

Jeff Meikle, Professor of American Studies

Dr. Meikle has published two book chapters in the past year! Very impressive.

"'You’ve Been on This Road Before': The Making of Laurie Anderson’s United States as an American Techno-Pastoral," in Transatlantic Currents: Essays in Honor of David E. Nye, eds. Jørn Brøndal, Anne Mørk, and Kasper Grotle Rasmussen (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 2021), 51-62.

"'Hoist That Rag': Tom Waits, the Uncanny, and the Old, Weird America," in An Unfamiliar America: Essays in American Studies, ed. Ari Helo and Mikko Saikku (New York: Routledge, 2021), 11-33.

Coyote Shook, Ph.D. Candidate in American Studies

Coyote has published artwork and essays in journals, magazines, is working on some unpublished art as well!

Salt Hill Journal, 47, features Coyote’s artwork

“The best $78.51 I ever spent: A knife just like my grandfather’s” The Goods (Vox)

“Where Have You Gone, Mrs. Duvall?” Beaver Mag, https://beavermag.org/coyote-shook-2/?fbclid=IwAR056HwxEW5vljNdeGcOgoI4EjmT5ROSDCrFGaBZDiPgY_HG7pW7-c0WlIE

Odalis Garcia Gorra, First Year Ph.D. Student in American Studies (also Social Media Team Editor and Co-Editor of this very blog!)

Odalis published two online essays, both amazing! One on cooking traditions and faith and one on Los Espookys!

“The Unreadability of Los Espookys,”Latinx Spaces, Februrary 2022.

Kameron Dunn, Ph.D. student in American Studies

llustration by Jason Stout

Kameron has been busy publishing in Slate, Texas Highways, as well as in an academic journal! Read his work here!

Holly Genovese, Ph.D. Candidate in American Studies

"What's Next, Southern Fried Chicken?" Confederate Memory and Racial Violence at the Postintegration University” in Invisible No More: The African American Experience at the University of South Carolina (University of South Carolina Press, 2021).

Holly is also publishing a popular Substack, “What is Much?,” where she rounds up books and films she loves as well as does close readings of everything from the Mary Kate and Ashley Canon to a Real Housewives memoir.

Kate Grover, Ph.D. Candidate in American Studies

Rocking the Revolution: The Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band and the Politics of Feminist Rock and Roll, Kate Grover, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2021 46:2, 489-512, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/710813

Kate Grover; Rock Trolls and Recovery: Revisiting Rockism via Miles Parks Grier. Journal of Popular Music Studies 1 March 2022; 34 (1): 29–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/jpms.2022.34.1.29, https://online.ucpress.edu/jpms/article/34/1/29/120446/Rock-Trolls-and-RecoveryRevisiting-Rockism-via

Dr. Gaila Sims, Ph.D. in American Studies (congrats Gaila)

Not only did Gaila recently defend her Ph.D. but she found time to write an essay with her sister for Believer Mag as well as a book review for H-Net.

Where We At, Believer Mag (co authored with her sister!)

Sims on Hall, 'Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts'

https://networks.h-net.org/node/12840/reviews/8609849/sims-hall-wake-hidden-history-women-led-slave-revolts

Dr. Randy Lewis, Professor and Chair of American Studies

From Dr. Lewis “It’s been a busy year for me, but I’m happy to share a few highlights. In September 2021 I started production of a documentary film called PRADA MARFA? about the most Instagrammed spot in West Texas, the artwork Prada Marfa, and how it has changed Marfa and become a Beyonce-fueled internet sensation in the process. Over the course of about four months from September to January, I cobbled together about two weeks of shooting in Valentine and Marfa, mostly standing on desolate Highway 90 and interviewing strangers about the art work. Think of it as a populist art criticism film essay that basically asks, “how do people respond to a controversial public art work?” It has required many drafts of a written essay, which provides my V/O; composing and recording a complex soundtrack; and cutting a 30 minute film that has probably 500 edits. Right now I’m soft releasing it on Youtube with the goal of bringing it to campuses—art history, Texas studies, American Studies, and geography classes would benefit from it. It’s been out for a few weeks, and it’s already being assigned to students at other universities!

What else can I say? Well, in January 2022 I spent a few weeks working with the Carceral Edgelands Project, writing about and raising awareness about migrant detention. Then in February 2022 I was invited to join a new collaborative writing project on the elements led by anthropologists Marina Peterson (UT Anthro) and Gretchen Bakke (Humboldt University, Berlin). Imagine 118 tiny books on the cultural lives of the elements and you’ll get the idea. More here. Around that time I wrote and recorded “Memories,” an original musical composition accepted in European anthology of contemporary Experimental Music called DATAPANIC #3 whose curators are based in Rome, Italy. I often use my recordings as a free form of soundtrack music, but this piece is too strange! I also published a very short essay called “Wandering as Method” in Imaginations: Journal of Cross Cultural Image Studies. It has images by my partner Monti Sigg, from a group project we did in Detroit/Windsor in 2020 that resulted in an exhibition at a gallery there. The big news in summer 2021 was that my film Who Killed the World? was named an Official Selection for Gbiennale 21, Melbourne, Australia. It was then released on Youtube where it already has reached 10,000 views and almost 200 “likes” despite literally zero promotion thus far. Free autonomous scholarly production is the future for a lot of the work I want to do!

Finally, I’m very excited that I’m starting a new research project on Telsa with my colleague Craig Campbell and a researcher in Berlin. Some portion of the work will end up The End of Austin, which I continue to edit—and which reached the amazing milestone of 250,000 page views this year!”

Zoya Brumberg, Ph.D. (Yay Zoya) in American Studies

From Zoya “I have a piece coming out in the spring/summer issue of SCA Roadside about UFO religions and the Integratron—I have the proof and can let you know/send the link when it goes into print.”

Dr. Erin McElroy, Assistant Professor in American Studies

A couple of articles/essays that Dr. McElroy had come out recently:

"Automating Gentrification: Landlord Technologies and Housing Justice Organizing in New York City Homes." Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, DOI: 10.1177/02637758221088868.

"Public Thinker: Sophie Gonick on Housing Justice and Mass Movements." Public Books, April 26, 2022. https://www.publicbooks.org/sophie-gonick-on-housing-justice-and-mass-movements.

Taylor Johnson, Ph.D. Candidate in American Studies

Taylor has been latch hooking and doing other fiber arts this semester while working on and defending her prospectus!

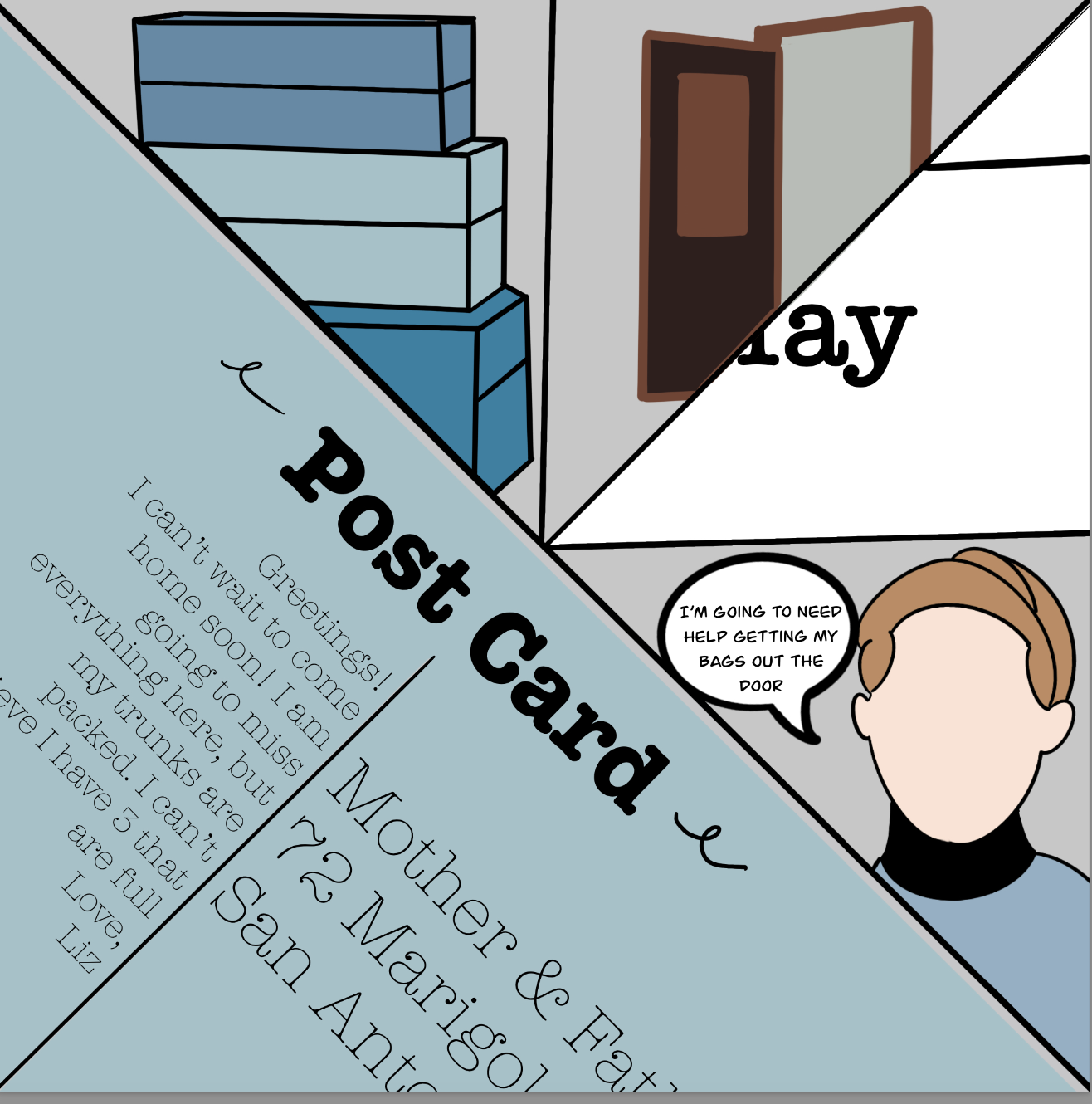

A comic about one of UT's early all-female dorms

Olivia Green is a third year American Studies and History major from Sugar Land, Texas with a keen interest in how history impacts our present day. Alongside her studies Olivia enjoys readings and exploring Austin. This semester she took AMS311s “American Comics” with AMS Ph.D. Candidate Coyote Shook.

Possession, Feminism and Bodily Autonomy in Horror

Reyna Ledet is a 2022 UT Grad who majored in Geography and Religious Studies. She enjoys analyzing the ways religion interacts with modern life, and the ways humans use stories to better understand themselves. This past semester, she took AMS311s “Haunting in American Culture.”

Fears of women’s bodily autonomy have fueled American moral panics for decades. The right of a woman to divorce, control her own money, and even to express her femininity has been controlled and limited over time. Even now, in 2022, the imminent overturn of Roe v. Wade promises to hurt women across America. However, issues of bodily autonomy are not the same between white women and women of color. Women of color and disabled women have historically faced forced sterilization on top of forced births, and Black women in America face an alarmingly high maternal mortality rate[1]. In media, confronting these issues directly can be difficult or painful; sometimes, framing this stolen control and the resulting trauma as supernatural can make catharsis over the issue more accessible. Possession in media often acts as a metaphor for the ways men violate and claim ownership of women’s bodies, but depending on how the narrative treats the possession, it can also indicate something about the politics the creators subscribe to - intentionally or not.

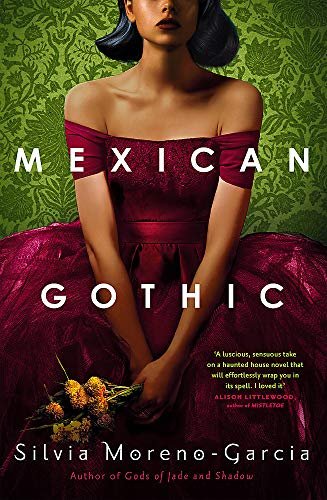

The two sources used here to illustrate this point are Jennifer’s Body, directed by Karyn Kusama and written by Diablo Cody, and Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia. Both sources are pieces of pop culture, and both involve women at high levels of creative control. Neither source involves the straightforward narrative of possession (a ghost taking over a body and using it to act on the material world), but both invoke possession as part of their narrative. Both sources also rely on genre to help tell their stories; Jennifer’s Body with the rape/revenge genre, and Mexican Gothic with gothic and cosmic horror. Each story plays with genre and references wider social forces, but ultimately, one story more successfully presents a nuanced understanding of bodily autonomy, and the comparison reveals the limits of a mostly white feminist perspective.

Jennifer’s Body uses possession to imply a sexual assault, and its muddled message tries to create an empowerment narrative by refreshing the rape/revenge genre. In the movie, an indie band called Low Shoulder sacrifices a high schooler named Jennifer to Satan to gain fame and influence. Because Jennifer is not a virgin, she dies and transforms into a succubus who feeds on people to survive. The movie frames the circumstances around Jennifer’s kidnapping and sacrifice sexually – she claims to be a virgin in the van on the way to the Devil’s Kettle to convince the band not to rape her, the band sings the song “8675-309/Jenny” by Tommy Tutone (including the line “I used my imagination, but I was disturbed”)[2] as the frontman of the band stabs Jennifer repeatedly in the stomach, and after the assault, he stands and breathes heavily as if he has just climaxed. Despite not directly depicting a sexual assault, the framing of the situation conveys the same effect. This assault transforms Jennifer into a demon, and she loses her empathy and begins to terrorize the town. The band gets to be the town heroes for most of the movie while Jennifer becomes the villain; only Jennifer’s guilt-riddled friend Needy understands the truth of the situation. The choice to use an indie band to commit this crime calls to mind the ways the alternative music scene preyed on young female fans in the 2000s[3]; it speaks to an awareness of broader social forces that might make a young woman vulnerable to attack. There is no doubt that the reason for Jennifer’s possession is meant to be a metaphor for a sexual violation of a woman’s body, but her atypical reaction to the trauma allows her to begin a revenge narrative that serves the audience on a shallow level.

The film tries to revamp the “rape/revenge” genre of films – movies in which a woman is sexually assaulted, and then someone seeks revenge for this transgression – but it undermines its message by clearly depicting Jennifer’s actions as evil. Jennifer’s Body follows the structure of a rape/revenge story, but it was created for teenage girls and reflected what teenage girls in 2009 might have needed to see in a horror movie.[4] While movies that depict women seeking their own revenge on their assaulter (such as I Spit on Your Grave) already exist, Jennifer’s Body spends less voyeuristic time on the assault and more time on Jennifer’s reaction to the trauma. [5]

“Jennifer’s Body and the Horrific Female Gaze” discusses how the movie does not reveal the actresses’ bodies to the audience, allowing them to retain their dignity;[6] many rape/revenge stories include a exploitative depiction of the rape to either titillate or horrify the audience. Watching Jennifer tear apart men who see her as sexually desirable without ever showing actresses nude may feel good to audiences who deal with misogyny and unwanted sexualization. However, despite being visually empowering, the message becomes more confused in the text of the movie.

Jennifer begins to consume young men that find her sexually enticing, including Needy’s friend from class, Colin, and Needy’s boyfriend, Chip. One of the themes Diablo Cody wanted to explore in her writing was the complex dynamics of high school female friendships[7], which explains why the film centers Needy and Jennifer’s relationship. However, the emphasis on the complexity of teenage girls creates problems for the attempt at an empowering rape/revenge format. Jennifer’s first victim lacks a support network in America, her second is grieving the loss of a friend, her third was just a young man with a crush, and her fourth had just gone through a confusing breakup with his girlfriend. None of these boys indicate a desire to violate Jennifer; to their knowledge, Jennifer consented to their sexual encounters. In the same way that Low Shoulder took advantage of Jennifer’s vulnerability, all of Jennifer’s victims had vulnerabilities she exploited to violate their bodies. At least one person in the community grieves each murder victim, some very intensely. While visually and out of context, Jennifer’s sexualized murders may feel like empowering revenge, the cruelty of her murders steals any empowerment audiences might get out of the movie. Jennifer’s demonic callousness puts her in conflict with Needy, which is more relevant to the plot than the fact that Jennifer was assaulted. For instance, Jennifer chooses to kill Colin because Needy expressed fondness for him, not because he deserved death (according to the movie’s moral code). Jennifer does not even get to enact real revenge by killing Low Shoulder; Needy kills the band with the demonic powers Jennifer inadvertently gave her. The focus on Needy’s journey reduces Jennifer to a sympathetic villain whose tragic loss serves as motivation for another character’s narrative. The subversions in genre the film succeeds at do not refresh the rape/revenge genre; they only create new thematic problems.

The movie also has problems with race. When asking if Needy and her boyfriend have just had sex, Jennifer asks if they have been eating “Thai food”[8]. Ahmet, Jennifer’s first victim, never speaks, only communicates in nods and head shakes. Jennifer also tells Needy to get her nails done by a woman who is Chinese[9] after seeing how damaged they got after Needy cleaned up Jennifer’s vomit. These “edgy” elements alienate Asian viewers, despite the creators’ desire to represent teenage girls as a population. Beyond the specific problematic elements, there are also structural issues with the narrative that further a white feminist perspective. If the creators intended to write Jennifer’s character as a power fantasy that punishes evil men, then she represents a fantasy wherein the predator is replaced rather than removed. In the same way that hiring more female CEOs will not solve the problems women on the whole face under capitalism, shifting an unfair power dynamic to include women still perpetuates the power dynamic. Modern audiences resonate with the queerness depicted in the film[10], but the positive representation does not erase the problems. Despite subverting some expectations, Jennifer’s Body does not address the issues its possession metaphor brings up and fails to consider broader societal ills that can amplify or change the implications of a sexual assault.

In contrast to the lack of consideration for race and other systems of oppression in Jennifer’s Body, the novel Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia uses possession as a metaphor for the long-lasting impacts of colonialism on Mexican women’s bodies, as well as how misogyny affects the colonizers and colonized in slightly different ways. The patriarch of the Doyle family, Howard, forces Noemi to consume mushroom spores by kissing her. This violation of Noemi's body turns her into an asset to the Doyle family by trapping her within the family manor. While there is no true ghostly possession, the mushrooms still exert influence over the bodies of the people of the house, so they act as a possessing force the same as any ghost. Notably, though, the mushroom spores exist as a part of the Mexican landscape that is exploited by outsiders. In the section of the Book Club Guide titled “A Letter from the Author,” Moreno-Garcia discusses the exploitation of indigenous people by mining operations.[11] Repeatedly, foreign powers forced locals to work the land only to steal from the Mexican landscape for the benefit of European empire. These exploitations displaced Indigenous people and killed many others. Howard Doyle turns the mushrooms into a method of profit and prolonged life, like the mineral deposits mined by Europeans, while actual Mexicans wither away. Only a select few Mexican people, such as Noemi, are allowed into the gene pool of the family to keep it from becoming too poisoned by incest, just as colonizers might marry an indigenous woman despite disrespecting their land, traditions, and autonomy. The Gloom of the mushrooms calls to mind the ways the haze of colonialism lingers over Mexico and its people - by stealing from and ruining the landscape, by traumatizing Mexican women over hundreds of years, and by allowing Mexican families to be torn apart by diseases. Howard’s dependence on the Gloom ties into this metaphor by positioning him as the colonizing parasite that sucks away the vibrance and resources of the indigenous community. The possession in this case has its sexual element - Noemi is expected to reproduce heirs to the Doyle family for Howard to possess in turn - but it also involves the inherent racism of the situation. Noemi and Catalina are not the only women in the book, though; Howards’s exploitation of his own family reveals the ways white women use power but still face oppression by white men.

Howard uses both Florence and Agnes Doyle to further his goals, but both women cause harm to Noemi and the Mexican people in the nearby village despite their own abuse. Florence acts as an antagonist throughout the novel by criticizing and belittling Noemi. When Noemi tries to escape with her cousin, Florence attempts to kill Noemi. Clearly, Moreno-Garcia did not intend to make the reader like Flroence, though there are glimpses of her humanity. She wanted to escape many years ago, clearly feels unhappy about her husband’s death, and the fruits of her labor are used by Howard the same as anyone else’s. Ultimately though, she serves the system she was forced into by Howard by participating in the conspiracy to trap Noemi. Florence inspires the audience to consider how she fits into a broader hierarchy in the narrative – she buys into Howard’s ideas through a combination of abuse and a sense of superiority. Howard treated Agnes in much the same way, only more egregiously. Agnes’ body is possessed by the mushrooms more thoroughly, but she in turn possesses the house and the people within it. Howard’s demands, expressed via the mushrooms, have nearly completely replaced her, and her only options are to beg for freedom and lash out. Like Jennifer in Jennifer’s Body, Agnes’ trauma transforms her into something monstrous, but her monstrosity is never mistaken for empowerment. “What had once been Agnes had become the gloom;”[12] Agnes’ perpetuation of colonial systems of power hurts her as much (if not more) as it hurts everyone else. Howard Doyle possesses the bodies of Agnes, Florence, and Noemi, but Agnes and Florence try to claim their own power by helping Howard. The unbalanced power dynamics empower no one, and only destroying the entire system can free the inhabitants of the house.

Like Jennifer’s Body, Mexican Gothic plays with genre to make points about the genres’ treatment of women. In contrast though, Mexican Gothic also has things to say about the ways oppressive power structures affect participants, even privileged ones. The “Gothic” in the title indicates that Moreno-Garcia intends to explore genre. For instance, the name “Howard Doyle” is a combination of H.P. Lovecraft and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, two giants in the realm of cosmic horror and mystery, respectively. Moreno-Garcia writes in the Q&A section of the Book Club Guide that “several of their stories contain racist elements”[13] (something of an understatement in Lovecraft’s case), nodding to the fact that while these genres are powerful and compelling to readers of many different kinds, oppressive elements exist in the foundations of these genres. In “The Girl in the Mansion,” Moreno-Garcia discusses the genre tropes that make up the building blocks of a mid-century “gothic” novel. The “formula” she discusses includes “a young woman, a big house, and a dangerous yet exciting man.”[14] The dangerous man in this case is Virgil, Catalina’s husband. In the vein of Byronic, gothic heroes like Rochester and Heathcliff, Virgil plays the role of a misunderstood man to fool Noemi into compliance. Virgil uses the Gloom to molest Noemi several times throughout the novel, but the reader understands the horrified sexual arousal Noemi experiences as the confused sexual arousal Gothic love interests of the past inspire in the heroines of old. When the story confirms that Virgil manipulated Noemi, the reader must confront the idea that the abuses excused by Gothic stories of the past are truly just abuses. Virgil represents an extension of postcolonial thinking that disguises itself as harmless or charming.

Francis Doyle is the sort of man who could be the protagonist of a cosmic horror story, but his subversive treatment by the narrative allows him the freedom to escape the horror. In his video “Outsiders: How to Adapt Lovecraft In the 21st Century,” Harris Brewis discusses the reasons that Lovecraft’s writing may resonate with queer viewers despite Lovecraft’s noted homophobia and extreme racism. One of the things that Brewis discusses is the way that Lovecraft gestures at the feeling of facing down an uncaring god[15]; the Doyles refer to Howard as a god repeatedly, and Francis’ family expects him to become Howard’s new host body (thus also indicating the ways that oppressive power structures violate the bodies of men). More broadly though, Brewis discusses the ways that Lovecraft expresses the feeling of being an outsider to a society that does not understand you. Oppressed people of many backgrounds feel the anxieties of existing in a world that actively does not care for your needs. Francis must exist with the knowledge of the horrors his family has committed even as they treat him without respect. Only when Noemi exhibits the strength to overthrow the order of the world as it stands can Francis emerge from the shadow of guilt over the actions of his family. As a white person, Francis must assist in the fight against the remaining issues of colonialism and imperialism, despite whatever difficulty he has in grappling with his feelings. The relationship between Noemi and Francis indicates another departure from genre; in cosmic horror of the Lovecraft variety, characters usually react to knowledge by going mad. Noemi, as a woman of color, gets to have a happy ending where she gets to navigate her trauma with two allies (her cousin and Francis). Brewis discusses The Shape of Water, directed by Guillermo del Toro, as a way Lovecraft can be adapted for a modern audience. He argues that allowing the monster humanity through its interactions with the minority characters represents a better way to approach the horror of the outsider – from the outsider’s perspective.[16] Noemi and Francis are both outsiders to the world of the Doyles, and their differences in power give them different strengths and weaknesses when fighting the evils of the Doyle family. In cosmic horror stories, happy endings represent a radical idea for outsider (or minority) characters, and Mexican Gothic stands as a more empowering story because of the choice to have Francis and Noemi make it out together.

Jennifer’s Body and Mexican Gothic both have things to say about the horror of a violation of bodily autonomy, and both have elements that work thematically in their favor. However, where Jennifer’s Body fails to express a coherent theme, Mexican Gothic considers the ways social forces combine to create a worse outcome for some women than others and recognizes where a system should be taken apart instead of reassessed. The “possessions” in their narratives both discuss the ways men take advantage of women, but “possession” inevitably means something different to a white woman and a woman of color based on their respective histories in the world. Also, Mexican Gothic understands the ways that men can be preyed upon too, while Jennifer’s Body unintentionally revels in the idea. Overall, to really understand issues of autonomy, pop culture should center compassionate and intersectional feminist works.

[1] Donna L. Hoyert, Ph.D, "Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last modified February 23, 2022, accessed May 8, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/maternal-mortality-rates-2020.htm. The statistics referenced are from 2020, where the maternal mortality rate for Black women was 55.3%. This data fluctuates heavily due to the relatively small number of maternal deaths yearly, but even in the two previous years, Black women had the highest rate among White, Hispanic, and Black women.

[2] Jennifer's Body, directed by Karyn Kusama, screenplay by Diablo Cody, 20th Century Fox, 2009.

[3] Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen, "How the pop punk scene became a hunting ground for sexual misconduct," The Brag, last modified November 23, 2017, accessed May 8, 2022, https://thebrag.com/pop-punk-internalised-misogyny-brand-new/.